One part history lesson, one part critical analysis, this series will examine the life and times of Captain America in an attempt to derive some deeper meaning contributing to the character’s lasting appeal. You can read Part 1 here. In this installment, we take a look at Cap’s origin and post-war growing pains.

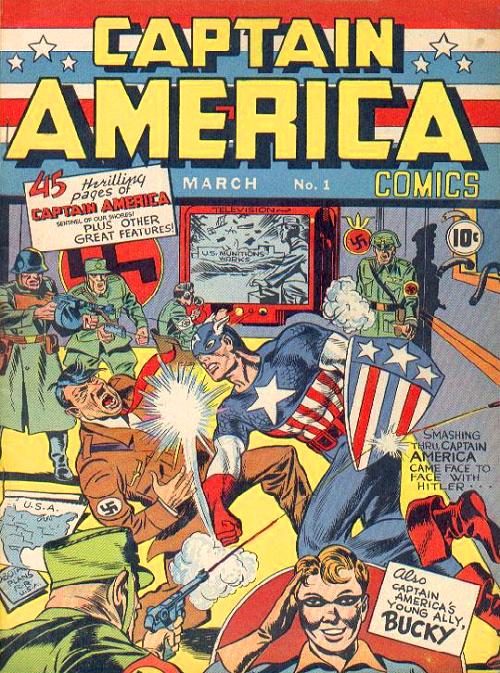

As originally conceived by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby in 1941’s Captain America Comics #1 from Timely Comics, the sickly, yet driven, Brooklyn kid Steve Rogers ingests an experimental serum and is transformed to the peak of human potential. With a physical form to match his boundless determination, he is America’s premier super soldier, leading the Allied Powers to countless victories on the front lines of World War II. With footholds in both superhero and war comics, Captain America was somewhat differentiated from his peers. On the whole, however, the series owed more to its genre magazine pulp predecessors than the capes ‘n spandex we’ve commonly come to associate with classic superhero tropes. Nevertheless, it — and the titles of its ilk — satisfied a market demand. Supporting the war effort via escapist fantasy. It was jingoistic propaganda played dead serious. And it was very much on the order of the day, as the first issue alone went on to sell over 1 million copies.

Having fulfilled his objective, Steve Rogers hung around for the early Cold War era, to diminishing sales and popularity. The public appetite for Red Scare menaces was not nearly so ravenous. With the industry moving away from war comics as the genre du jour, Captain America faded into obscurity. This is where Steve Rogers’ story could have ended, a curio in early comics history. Even if his creators could have anticipated the explosive rebirth and reconceptualization of the American superhero in the 1960s, they could not have predicted Cap having a place alongside these new creations. But early Marvel Comics architect and visionary Stan Lee was never one to let a good idea rest.

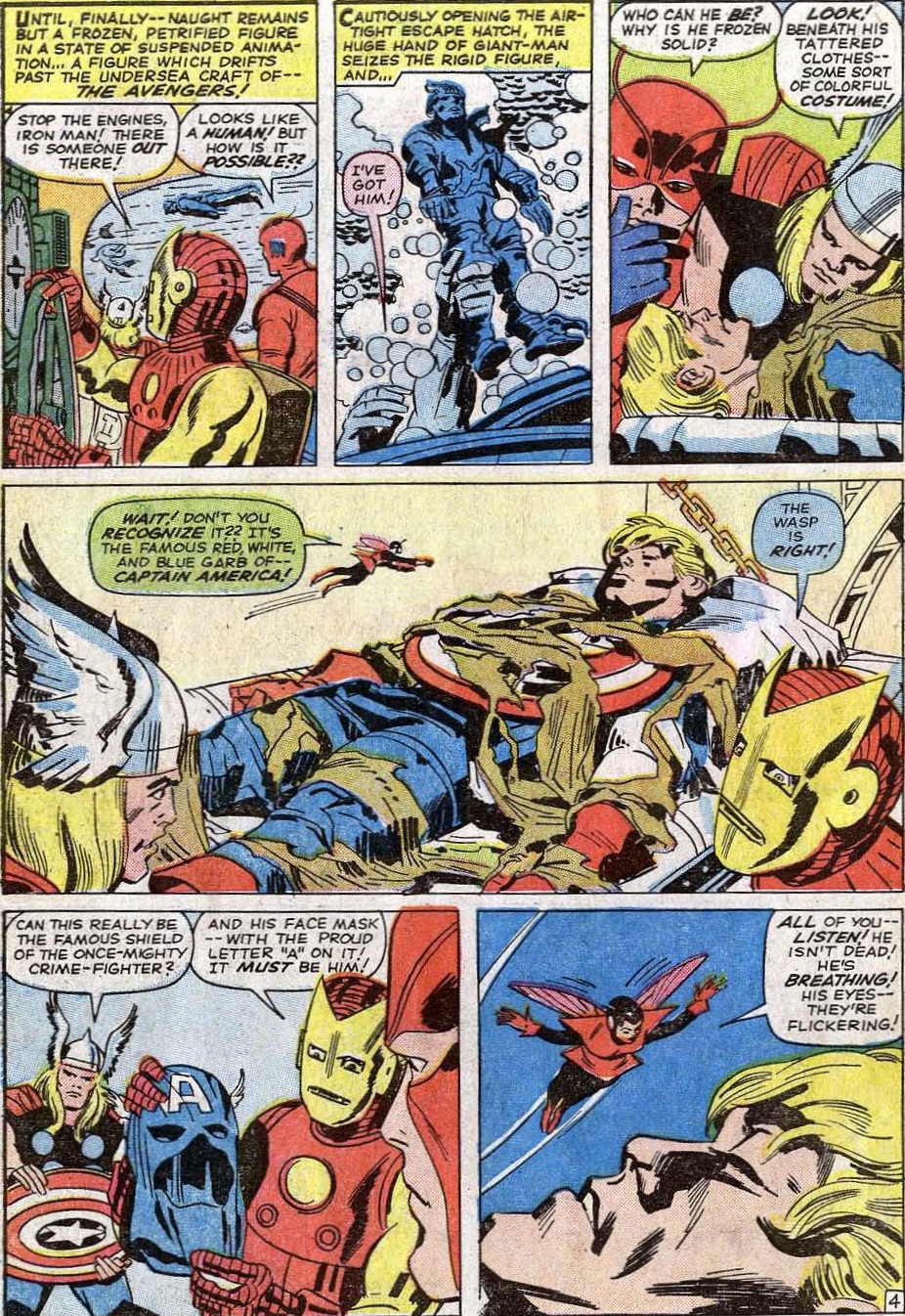

Bringing Captain America into the nascent Silver Age Marvel Universe turned out to be a stroke of brilliance on the part of Stan Lee. Character-wise, there were many paths Lee could take in marking Steve Rogers as a man out of time; more telling, though, was the manner in which he could be used to demonstrate just how different the new Marvel U was from its predecessor in Timely — not to mention all of its contemporaries. Himself a prominent former Captain America Comics writer (the series was in fact the source of Lee’s first published comics work), Lee used Steve Rogers’ valiant last stand and teen sidekick Bucky’s demise as a line in the sand between the old and the new. A bit of revisionist history which had the effect of excising Steve Rogers’ post-war activities, this formative event would provide Cap with the competitive edge intrinsic to every new Marvel hero: a tragic backstory and need for atonement.

The Living Legend was more akin to the Living Anachronism upon his 1964 revival. His teammates in the Avengers reacted to him with as much wonder and curiosity as he regarded his own changed surroundings. A story about Cap’s failure to accept and adapt to the Age of Heroes could have reinforced Marvel’s commitment to their new direction, in its own way. If he had been played straight, plucked directly out of 1941 and utterly tone deaf, it would have devolved into parody (intentionally or otherwise). But Lee clearly still had some affection for the character and was not content to dismiss him as an artifact. Instead, Cap’s chronal displacement made him the perfect foil for the upstart heroes of the Marvel Universe, in addition to positioning him as a loftier meta commentary on the times, and how they are a-changin’. And thus began Captain America’s long history as a vehicle for exploring the issues of the day.