The launch of the WWE Network is a game-changing move, but it is at the risk of abandoning the pay-per-view market that helped shape the modern pro wrestling business

When I was an easily influenced wrestling fan as a kid watching the World Wrestling Federation’s Superstars or Wrestling Challenge programs back in the early 1990’s, my favorite part of the show on most weeks would surprise many. The wrestling itself had a multitude of squash matches that exhibited the dominance of the top names. The interview segments on the podium or at the Barber Shop could bring about some memorable moments, too. Even the old school split screen promos by wrestlers to promote a feud or a future match were random and fun to watch at times. Sometimes the 10-year-old me found it strange how the announcers seemed to be so far away from the roaring crowd in the background every time they introduced the shows, realizing much later that they were usually talking in front of a green screen. But the segments I would always “mark out” for when they came along on those Saturday and Sunday mornings were the pay-per-view event updates, where personalities like Mean Gene Okerlund, Sean Mooney, or Lord Alfred Hayes would keep tabs on the card rundown for the WWF’s next big event, whether it be SummerSlam, the Survivor Series, the Royal Rumble, or the grand daddy of them all, WrestleMania.

I can still remember with delight the stills of each WrestleMania with the guitar music blaring in the background as Mean Gene would announce every “officially signed” match for the card, with a bonus feature of taped interviews from the combatants thrown in there just for kicks. What always fascinated me about those special reports was where they always took place in what was often called the Control Center, with its wide array of television monitors, button grids, and dimly lit hallways. You could not help but float off and stare at the dozens of images of WWF programming that would flutter on the screen simultaneously, whether it was the same match being edited by one of the faceless production people sitting down or if it was simply different shows being played for the sake of glamorization. WCW even did a similar event report segment on their weekly shows with Jim Ross at what they dubbed the Command Center, but it was usually just J.R. in front of a green screen for 10 minutes. Many different promotions had hubs or fictional bases of operations, but due to budget, they were usually unimaginative scenarios like Gordon Solie in front of a backstage wall at Georgia Championship Wrestling or even right next to the entryway like the NWA did on World Championship Wrestling.

Vince McMahon’s higher tech version of the setting was uniquely futuristic and deliberately filled up the TV screen with all things WWF, an entire facility seemingly dedicated to its footage, pay-per-view telecasts, and likely all its archives. The concept of the original Control Center was eventually phased out in the mid to late 1990’s as we got used to Todd Pettengill shilling toys in what looked like a New York apartment on Mania or Dok Hendrix doing dance moves on the Action Zone. By the time I was in high school and they brought back the setting for their call-in/recap show Livewire, I was not nearly as enamored with the actual setup as I was in years past. But even as I grew older and the Attitude Era was in full swing at the turn of the century, I still looked back at the times with Lord Alfred would promote all the WWF shows and merchandise at the start of whatever Coliseum Home Video I rented and wished I could have been a fly on that studio wall. The physical concept became outdated over time, but the dream still remained: What if we as wrestling fans were able to access all of the WWE’s programming, including the shows that they air on a weekly basis, without the hassle of buying overpriced videos with clam shell boxes or having to begrudgingly call our cable company to order a pay-per-view? As new age technology advances itself further and further into the zeitgeist of our media consumption, it was more plausible than ever for WWE fans be able to do what the 10-year-old me dreamed about on Sunday mornings: A permanent invitation inside the Control Center (Or, as Dusty Rhodes would have lovingly called it, the Mothership).

That childhood wish of unlimited viewing access is now on pace to become a reality starting on February 24th after World Wrestling Entertainment made the long-anticipated announcement that the WWE Network would launch that day as a digital app with the first live material streaming immediately after Monday Night Raw was over. Fans knew it was going to be an epic event after word got out that appearances would be made by not only Vince, but also John Cena, Shawn Michaels, and Steve Austin at the Cosumer Electronics Show. Just as the WWF buying WCW and ending the Monday Night War took place in the middle of a resort at Panama City Beach, how fitting is it that the announcement of the WWE Network (perhaps its biggest move since buying its competition back in 2001) occurred at another getaway lounge, the Wynn Hotel in Las Vegas? It was there that Chief Marketing Officer Michelle Wilson was the first to announce that all of the pay-per-view events (including WrestleMania) would be instantly available, including all WCW and ECW events. On top of that stunner came the price point of $9.99 per month with a six-month commitment, a cost so reasonably cheap that even the most grizzled of wrestling fans are squealing with joy to get it.

If you’re a dedicated fan and need any major wrestling PPV that occurred in the past three decades, you can toss out those old VHS tapes or hazily burnt DVD copies you would have to sort through and have any random event available to you literally at the tips of your fingers. As Michelle Wilson said to finish up her eye-popping presentation, the WWE Network is over the top by its very definition. The only complaints I could find on Twitter and Facebook the morning after the announcement was the fact that they had to wait 46 more days before they could get their hands on it. What seemed like a dwindling fantasy in years past has finally mirrored actuality: There is now a de facto home for the WWE fan base. For fans of the current product, previous fans of WCW and ECW, or supporters from any era that came into existence since the company’s 50-year history, the WWE Network is now your subscription-paid sanctuary. If WWE were compared to religion, the WWE Network would be the Vatican, a manifest destiny the likes of which never seemed possible even a couple of years ago.

The original plans for the Network itself actually began as somewhat of a false start in October of 2011 when the WWE began airing splashy ads set to a remix of the song “Cinema” which promoted that the Network would arrive sometime in 2012. There was even a countdown clock put on WWE.com which was set to end on the day of WrestleMania XXVIII in Miami, FL, but the business trades were still mum about any deals struck with cable providers or on demand service hires in the company. It remained all quiet on the Network front in early 2012, and with no announcement seemingly in sight, the countdown was taken off of the web site and the idea was tabled for the time being. Quarterly conference calls would make mention that the WWE Network was still in the planning stages, but there was no promise of available content, launch date, or whether or not it would be optioned to satellite providers as a linear channel.

Rumors started swirling that when WWE corporate pitched the idea to cable providers like DirecTV and Dish Network over the past two years, the reception was lukewarm to say the least. That response should come as no surprise when you consider the number of lost money at risk for these third-part satellite providers who have thrived on the WWE’s pay-per-view revenue stream that has been around since pay-per-view’s forefather closed circuit television (CCTV) was even put to use for the purposes of entertainment. The first actual closed circuit television was invented by famous engineer Walter Bruch in 1942 in Peenemünde, Germany, so that operators of the V-2 rocket (the first long-range ballistic missile) could observe its launch from a safe distance. CCTV has since been used over the years for the sake of surveillance or laboratory experiments unsafe for human presence, but in the 1960’s and 70’s it was used at times to access an exclusive feed to a specific location for major sporting events like the first Muhammad Ali/Joe Frazier boxing match in 1971 or even rock concerts from acts like the Rolling Stones.

Promoters saw potential in this tool for a while and it was Vince McMahon’s father, Vince Sr., who orchestrated a closed-circuit viewing of a much-publicized match between Ali and Japanese wrestling grappler Antonio Inoki on June 26, 1976. The match took place in Tokyo, but Vince Sr. had the bright idea to access the telecast and exclusively broadcast the bout at Shea Stadium in New York as the main event of a live card that included Andre the Giant facing former boxer Chuck Wepner. The Ali/Inoki match was a disaster that drew the throwing of trash in the ring by the Japanese fans, but McMahon came out smelling like rose after attracting over 32,000 people to attend the Shea Stadium event mainly to watch a television event that was simply not available anywhere else. That curiosity became an outright enterprise with the dawn of pay-per-view television. Pay-per-view was technically invented back in the early 1950’s with the Zenith Phonevision, which operated by de-scrambling broadcast signals during the station’s off-time thanks to IBM punch cards. It was tested out for three months in Chicago, but the F.C.C. refused to grant a permit after the test run was over.

The first official pay-per-view stations were used in San Diego, CA, and Sarasota, FL, in the early 1970’s, one of which showed two movies per week. Those stations shut down quickly as cable television via satellite and Home Box Office came on the scene. The first genre that laid the foundation for pay-per-view was boxing, which was arguably the premier sport in the United States leading up to 1975, when Ali and Frazier had their third and final fight “The Thrilla in Manilla.” That fight garnered a number of buys, but it was Sugar Ray Leonard who quickly became the golden boy for cable companies looking for some extra buck as his fights with Robert Duran and Thomas Hearns in the early 1980’s made well over 150,000 buys each. One of the pioneers for pay-per-view was a Viacom executive named Pat Thompson, who helped set up the Leonard/Hearns fight and wanted to expand pay-per-view programming through other avenues. More boxing fights were added along with Broadway plays, football games, and pro wrestling events. Once Thompson left Viacom to create Sports View, there were a multitude of national pay-per-view stations ready to roll out on cable. By 1985, there were four cable channels launched strictly for pay-per-view, including Viewer’s Choice and Request TV.

By this time, Vincent K. McMahon had become the sole owner of the WWF in place of Vince Sr., who had passed away the previous year. With the Rock ‘N Wrestling movement and Hulkamania shooting the WWF’s popularity to all-time highs nationally, McMahon utilized his cable allegiances to create the WWF’s first-ever annual super card with WrestleMania on March 31, 1985. The event took place at Madison Square Garden, but reports have said that it was watched by over 1 million people on closed-circuit television (The Crocketts used a similar move for Starrcade in 1983 at different closer-circuit viewing areas in the Southeast, but it was much more limited than the first WrestleMania). Not only were fans driving out to a local auditorium to see Hogan and Mr. T at WrestleMania, but many ordered it from the comfort of their own homes as it was the first-ever WWF event to be available in limited markets on pay-per-view. Many debate whether the first official WWF pay-per-view was WrestleMania I or The Wrestling Classic in November of that year, but the red carpet had nonetheless rolled out for the WWF and pay-per-view to walk down the aisle.

The union of professional wrestling and the pay-per-view market was a perfect coupling: a niche audience for a niche service. The relationship strengthened even more after the epic WrestleMania III in 1987, which set an indoor attendance record of over 93,000 spectators and generated an estimated $10 million in pay-per-view revenue. It did not take long for the WWF’s competition to get in on the action as World Championship Wrestling provided shows like Starrcade, Bunkhouse Stampede, The Great American Bash, and Halloween Havoc on pay-per-view. McMahon pulled a coup on the Crocketts when he booked a newly minted pay-per-view event, the Survivor Series, on November 26, 1987, the same night as Starrcade, and forced cable providers to choose one show over the other for their air time (most of them chose Survivor Series). What was once only one annual event had ballooned to four by 1988, along with three from WCW and the disastrous AWA/World Class collaboration Superclash III. While WCW’s pay-per-view buyrates (by which case a 1.0 buyrate generally equals 400,000 buys) were decent enough to keep it going, the WWF’s buyrates were tremendous from the outset and remained above 3.0 (over 1.2 million buys) until 1991.

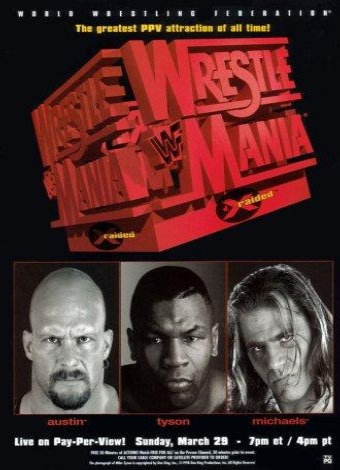

By the time we reached 1995, the WWF began running one pay-per-view every month of the year while WCW, which had just signed big names like Hogan and Randy Savage under Eric Bischoff, had eight of them, with more to come. As the war between WWF Monday Night Raw and WCW Monday Nitro heated up and the cable ratings rose in the late 1990’s, so did the demand for more product on pay TV, evident by the fact that in 1997 alone, there were 12 pay-per-views from the WWF, 12 from WCW, and 3 from the Paul Heyman’s renegade ECW promotion. The hunger for pro wrestling in popular culture had been revitalized during the heyday of the nWo and the WWF’s Attitude Era, and the pay-per-view numbers exhibited that, with WCW hitting an all-time high for Sting vs. Hogan at Starrcade ’97 and WrestleMania XIV reaching a buy rate of 2.32, its highest in six years. Even makeshift promotions that had absolutely no business running wrestling shows got their foot in the pay-per-view door because of the thirst for more content (Heroes of Wrestling, anyone?) What was originally envisioned as an bi-annual specialty nearly became a weekly to-do list on Sunday nights for the sleepless.

The Monday Night War ultimately yielded WCW and ECW as its biggest casualties when they were sold hand over fist to Vince McMahon, but the biggest losers from a spending standpoint may have been the wrestling fans who at one point were so inundated with pay-per-view content that it almost became impossible to afford. As inflation rose over the years, so did the price of these various pay-per-views, with WrestleMania costing even more as the years went along. WWE was in the unique position of being the only game in town with mountains of freshly bought non-WWE archives at their disposal but with little idea of what to actually do with it. As they continued their monopolization of professional wrestling in the U.S., the tide of wrestling’s national popularity broke and just like the sinking ratings on Raw and Smackdown, the buy rates showed that trend. Perhaps it was the loss of legitimate competition to up the ante or customers scoffing at the eventual price increases, but in 2003, the only pay-per-view wrestling event that exceeded 400,000 buys was WrestleMania XIX.

The Mania dependence factor became more noticeable than ever before for the WWE. As a company that went public on the stock market in 2000, WWE was bound to conducting quarterly financial reports and the report that covered WrestleMania’s financial success was usually the make-or-break for WWE’s forward-looking stock value. The non-WrestleMania buyrates were steadily declining, and it almost became comical to find out which excuse Vince would use in his quarterly conference call to explain to shareholders why the numbers were down. The disparity was crystal clear in 2005 when WrestleMania 21 in Los Angeles garnered a then-record 1,085,000 buys, but the only other WWE pay-per-view that year that did better than half that number was Summer Slam. Pay-per-view remained a vital revenue stream for WWE despite the downward trend and boosted the bottom line by raising the prices on two occasions ($39.95 in 2006 and $44.95 in 2009) in the past seven years. The grand daddy of them became a grand pain to wrestling fans’ bank accounts and challenged the allegiance of many when it was announced in 2013 that WrestleMania XXIX would cost $59.95 in standard definition and a whopping $69.95 in high-definition.

But as WWE corporate names like George Barrios and Perkins Miller made more noise at different functions outlining the backbone for an eventual WWE Network, the project that seemed like a poorly rushed pipe dream in 2012 looked like it was reaching the surface. Surveys to fans on their web sites and social networking tools asking fans what they would like on the Network were taken in, but most fans were cautiously optimistic about what the WWE would actually offer in contrast to the pay-per-view model that they had been so reliant on since the early 1980’s. Many WWE fans believe that it would resemble the digital Fight Pass from Ultimate Fighting Championship, the MMA promotion that has recently overtaken WWE as the king of pay-per-view. UFC’s Fight Pass contains lots of archival footage from past fights and B-level cards, but the big time pay-per-view cards will still have to be ordered through your satellite provider. WWE knew that fans and business experts were anxiously awaiting their next move on the chessboard to see what they would do with their 24/7 platform, and what they came up with was a figurative checkmate.

If the cable providers were unwilling to tag with WWE in their quest to launch a platform, then they were going get thrown over the top via digital media. It is through that crossroads that we have reached what happened this past Wednesday with the announcement of the WWE Network app, a move that truly is a changing of the guard in terms of medium. We are so used to hearing sponsors and talking heads spew out words like “groundbreaking” and “game-changer” as if they are throwaway phrases, but in the case of the upcoming WWE Network, it truly does break the mold when it comes to the way the company is going to operate in the near future. Vince McMahon always had a vision of not just bringing his product to the world but bringing the world into his product, gathering fans of all types and congregating them into a universe all his own. With this significant move, we have an official colonization for wrestling fans soon on a global scale, a true gathering of the stars in the WWE Universe. By cutting out the middle man, which in this case would be the cable providers who benefited for years from WWE’s excessive pay-per-view prices, the fans’ enjoyment of the product will transition from being at a steep expense to being at their leisure. If the past model of weekly TV programming served as a window into the commercial-free WWE Universe on pay-per-view, then the WWE Network is the all-encompassing planet around which the universe revolves.

The suspension of disbelief that I gladly used as a kid when I dreamt of an epicenter for all WWE fans to indulge in my fandom turned into flat-out disbelief as news of the Network’s available content stunned me silent. Those fans who do not care for the current stars like John Cena or C.M. Punk can still join up at a fair price to jump in a time machine and enjoy whichever era it was that defined their love for the business, whether it be Hulk Hogan, The Rock, Steve Austin, or even Bruno Sammartino. Members of Cena Nation, Hulkamania, and Austin 3:16 will be able to conjoin in this globalized village without the hassle of leaving their preferred nest. But by proudly comparing the costs of the app to the pre-existing pay-per-view format, WWE seems to be openly inviting their niche fans to ditch that old model and trade it in for their shiny new toy. Cable providers are not pleased with this announcement, and it is hard to blame them due to the fact that they will eventually lose one of their biggest pay-per-view cash cows. With WrestleMania XXX in April being announced as the very first pay-per-view event available on the WWE Network, it comes as no surprise that the cable companies who previously turned the Network down feel like they are getting left at the altar by their loyal spouse. DirecTV issued a statement shortly after the announcement that was critical to say the least, throwing jabs at WWE’s declining audience and vaguely threatening to pull its shows from their schedule. I would expect providers like Dish and Time Warner Cable to step in line with the motif that either the WWE needs to drop their pay-per-view event prices in order to stay reasonable in comparison to the Network’s offerings, or they will simply stop showing them.

Just like the Network’s development and all other corporate entanglements, we probably will not see these decisions by cable providers concerning future WWE pay-per-views until months or even years after the Network is already up and running. No matter what the fallout will be, there is no doubt that the announcement of the WWE Network is a generation-defining moment in the company’s history. However, any time something occurs that is truly ground-breaking, there is bound to be collateral damage as that ground breaks along with those who slip through the cracks. That falling man in the case of professional wrestling might just be the pay-per-view business model, which still harvests UFC super cards and championship boxing fights along with movies on demand and may be more than willing to sever their own ties with WWE if buyrates sink low enough in favor of joining the Network. The WWE Network officially moves the company’s direction into the post-modern by compartmentalizing their entire universe into a magic box, but when it comes to their soft exit from the pay-per-view market under which they have thrived for so many years, they may have opened up Pandora’s Box.