Mild-mannered reporters by day, Greg Phillips and Nick Duke share an intense love of comic books that has made them the Hard-Traveling Fanboys. Over the course of their travels through comicdom, they have encountered numerous stories via the wonder of trade paperbacks and graphic novels. Once a month, Nick and Greg will review one of those collections in The Longbook Hunters.

Nick: Welcome once again to our monthly trip through the world of trades and graphic novels. This time out, we’re taking a look at the 2004 DC miniseries Identity Crisis, written by Brad Meltzer and penciled by Rags Morales.

Greg: We’ve reviewed several historic collected editions within these columns since Place to Be Nation’s inception, but none have been quite as controversial or divisive among the online comics community as this one.

Nick: Very true. Rather than offering a universe-spanning, reality-threatening event like most crossover miniseries, Identity Crisis told a story with a much narrower focus, and a much more morally ambiguous version of DC’s premier heroes.

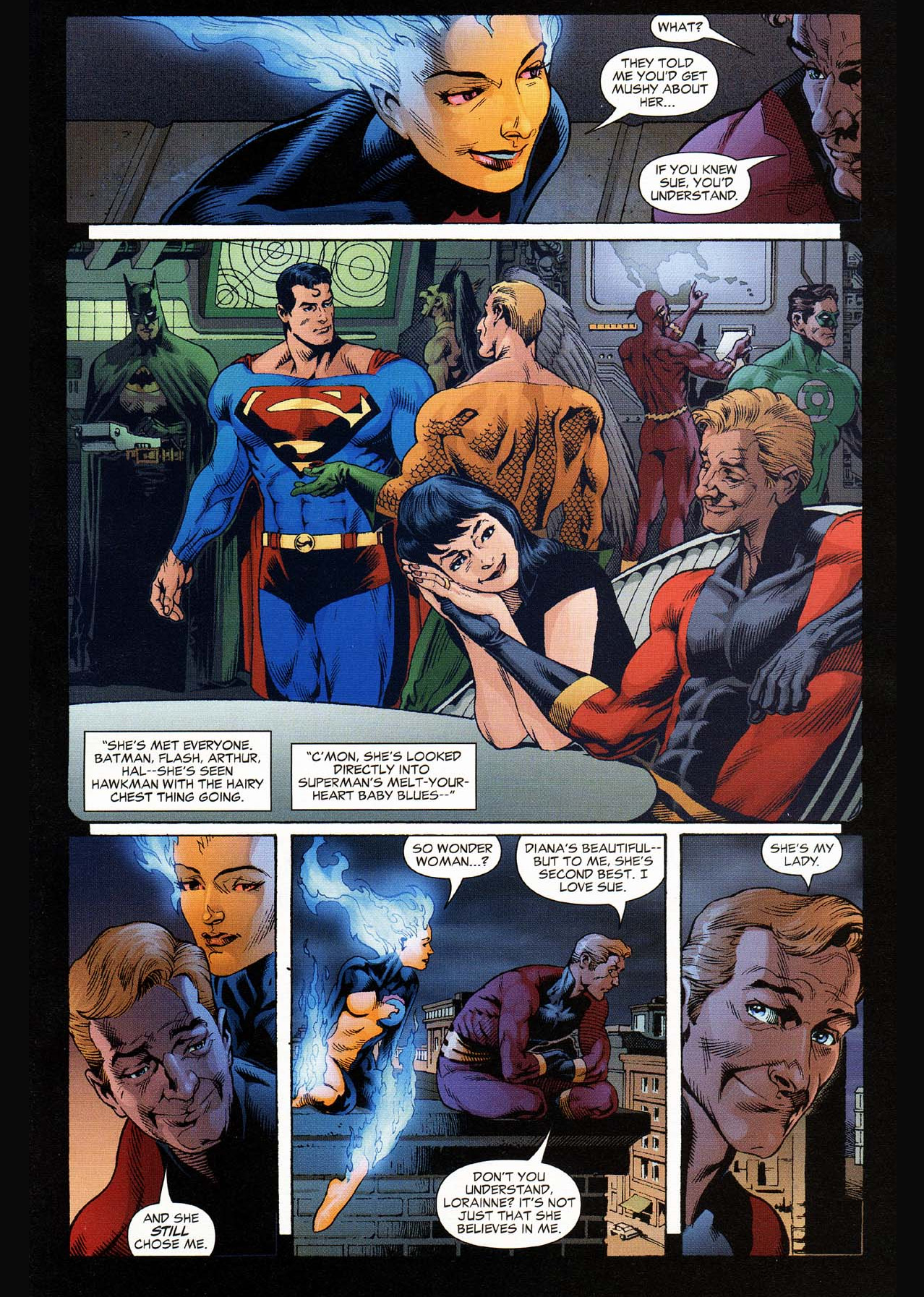

The story focuses largely on the death of the Elongated Man’s wife, Sue Dibny, and the Justice League’s search for her killer’s identity. Along the way, secrets from the League’s past are revealed and dynamics between characters are shifted so much it’s difficult to imagine the League carrying on as if nothing had happened.

Greg: But before we delve into the pros, cons and ethics of “Identity Crisis,” let’s put the book into context. In my view, DC Comics reached something of a creative zenith in the mid-2000s, along with an almost unprecedented level of connectivity between the publisher’s flagship titles.

That period of DC’s modern era can be argued to have begun at several different places — Mark Waid’s “Tower of Babel” story within the pages of JLA, Ed Brubaker and Greg Rucka’s “Batman: Fugitive” or Jeph Loeb’s “President Lex,” for instance. While the building blocks are certainly present in those stories, it was arguably this story by famed novelist Brad Meltzer that formed the thematic backbone of DC’s next several years of storytelling.

Its effects were felt in the buildup, execution and followup to the sprawling Infinite Crisis event, but ramifications continued to bleed through the rest of the post-Crisis, Pre-New 52 DC Universe.

Nick: At the core of much of DC’s storytelling during that period was tension between the so-called “Trinity” of Batman, Superman and Wonder Woman. The seeds of that tension were sowed in many different stories, but it’s here that we’re treated to seeing one of the major reasons for Batman’s distrust of his fellow Leaguers. The events of “Identity Crisis” are also felt during the lead up to “Infinite Crisis,” when the League finds itself fractured and divided.

Greg: While I’m not a fan of providing detailed spoilers for the books we review, discussing this particular work requires a level of plot revelation. As you mentioned, Sue Dibny, one half of one of DC’s longest-lasting and most iconic couples, is murdered in the opening chapter of the book.

Much of the book’s conflict, and its long-lasting impact, is felt in the ensuing investigation from pretty much every superhero in the DCU. It’s revealed, through the course of the mystery, that the original Justice League abused its power in dealing with a supervillain who had uncovered the League’s identities and sexually abused Sue in the process. The league not only wiped this knowledge from the villain’s mind, but altered his entire personality, making Dr. Light into the goofy, unthreatening villain he was throughout most of the Silver, Bronze and Modern ages of comics.

Nick: This mind wipe is discovered by Wally West and Kyle Rayner, who both take the news pretty hard. As the two youngest members of the league, they both hold their teammates in very high regard and have viewed them as mentors of sorts. Both are also troubled by the fact that their predecessors, Barry Allen and Hal Jordan went along with the morally objectionable plot. In the case of Barry, Wally undoubtedly viewed him as a man to model himself after, and the young speedster has trouble reconciling this decision with the Barry he once knew. In Kyle’s case, he has spent much of his League career hearing how great, courageous and bold Hal Jordan once was, making it all the more surprising to hear that in this instance, Hal didn’t stand up to the rest of the League.

However, as it turns out, the mindwipe of Dr. Light is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the questionable actions of a handful of League members.

Greg: Indeed. For when the legendarily weary-of-power Batman refused to go along with their plan to mindwipe Light, the other Leaguers have another vote — this time to mindwipe Batman, forcing him to forget the entire experience. This vote proved more divisive amongst the original team, but it’s perhaps the action that caused the most long-term damage.

If this sounds like a lot for a seven-issue miniseries to tackle, that’s because it is. The in-fighting amongst the JLA takes place as merely part of the main story, which centers on the heroes’ attempts to find Sue’s murderer and the murderer’s attempts to go after other heroes’ loved ones.

It’s a pretty engrossing mystery from the onset, particularly when I first read the book a decade ago. The ultimate reveal came as a huge shock, and Meltzer proved adept at crafting a believable mystery.

Nick, did you know the details of the story before reading it recently, and if so, did that affect the suspense at all?

Nick: I knew the basic plot, but luckily, I did not have the twist ending spoiled for me. I also knew about the mindwipe aspect of the plot, but that’s to be expected since it was such a key point of DC continuity over the last decade and this was my first read through of Identity Crisis. Overall, I felt like the suspense of the murder mystery and the constant wonder of whose loved one would be targeted next kept the story intriguing and nerve wracking.

Greg: Speaking of which, many characters met their end in this miniseries. Heroes, villains and supporting characters alike were in danger throughout. Which character’s ultimate fate affected or interested you the most?

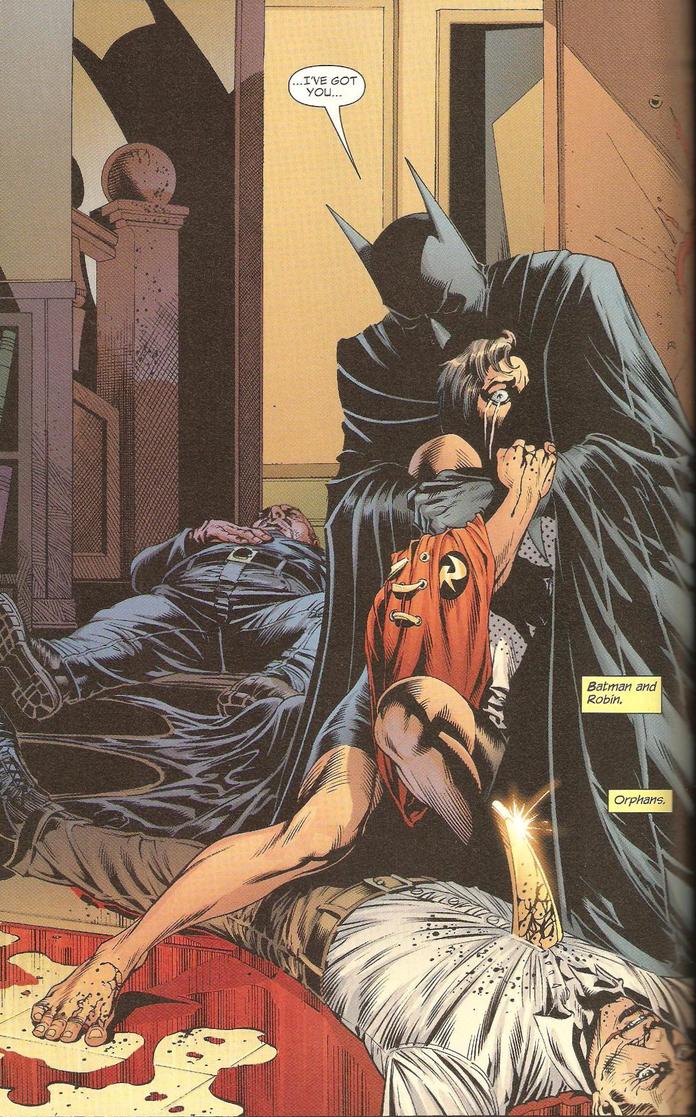

Nick: It’s a close race between Sue Dibny and Jack Drake. I never had any deep attachment to either character, but Meltzer and Morales do a brilliant job of conveying the pain that Elongated Man and Robin feel as a result of their loss. The scene of Batman attempting to comfort Tim after his father has been killed is one I had never seen before, but will now love as one of the enduring Batman images in my mind. Sue Dibny’s death, meanwhile, provided Morales an opportunity to run wild with Elongated Man’s facial features. He toys with the idea that immense emotional distress would cause Ralph to lose control of his elastic skin, and we get some great images of Ralph at his wife’s murder scene and her funeral with his jaw drooping to his chest or his skin flowing around his hands as he covers his eyes.

Greg: Oh man, those scenes of Ralph’s grief represent the pinnacle of Morales’ career, in my eyes, and some of the best visual work I’ve ever seen in a superhero book. It was totally heart wrenching in all the best ways. It’s one of the shining examples of comics’ ability to uniquely hit the same emotional tones as other art forms.

And, like you, the Jack Drake subplot stood out to me as well. So often (especially during the era of “Identity Crisis”) we’ve treated to the cold, detached post-Miller Batman. It was moments like his fatherly comfort to Tim Drake that reminds us that underneath it all, Bruce Wayne is a good man trying his best to do the right thing.

Nick: I feel like there have been numerous moments of Batman being a father to Dick or Damian that have stood out to me, but relatively few such moments with Tim. This was an extremely effective one, however.

Greg: Morales seems to thrive on the slower, more emotional moments in superhero books, and “Identity Crisis” certainly allowed him to shine in that regard. The facial expressions throughout the book are stellar, with those of Elongated Man, Tim Drake, Batman, Jean Loring and the Atom standing out. Unquestionably, the book doesn’t work as well without the sheer passion with which Morales draws these characters.

I’m glad to hear the mystery worked as well on you as it did on me. I remember being stunned at the time, despite having only a passing knowledge of Ralph and Sue at the time I read it.

Given that the book relies on the relationships between all these major characters, how well do Meltzer and Morales introduce new readers to these bonds? For me, I felt like the art and words combined to create an uncommonly strong connection with Ralph and Sue in the very first chapter.

Nick: It’s strange because I feel like the book does a better job of making new readers understand the relationships between characters than it does the characters themselves. For example, I feel like readers who had only a passing knowledge of Green Arrow or Hawkman aren’t really treated to a very definitive or well-rounded version of these characters. However, Meltzer does a great job of establishing that Ralph and Sue aren’t just in love — they have perhaps the most happy and functional relationship of all the “supercouples.” The same goes for the father-son relationship between the Drakes. It’s clear, in the course of only a few panels, that the two have a decent relationship that both wish were better. He also conveys the complicated past of Jean Loring and Ray Palmer, the Atom, fairly well to readers who are unfamiliar with the pairing, much as I was going in. So, while the characters themselves may feel a bit unfamiliar or off-center from their normal characterization, the bonds between them are demonstrated as well as ever.

Greg: I have to confess I rather enjoyed the Hawkman-Arrow banter in this one, but I agree with your premise — this is clearly a story based less on individual characters than on the relationships that encompass the characters. Not just the romantic pairings, either. The dynamics between Leaguers such as Zatanna and Batman, or even between the villainous Captain Boomerang and his son, are also explored.

I guess now is as good a time as any to transition into a discussion of some of the controversy surrounding this story. First off, this was a markedly darker story than had been seen in mainstream DC Universe crossovers to this point. While death was certainly commonplace, rape and serial murder within the superhero community were topics only rarely addressed outside the metafictional works of Alan Moore.

For better or worse, “Identity Crisis” started DC in a darker and more “adult” direction. So let’s ask the most obvious question: did Meltzer take things too far with this tale?

Nick: It’s not an easy answer, but I’ll say yes. But that isn’t a bad thing. I’d say that taking things too far was the entire point of this story. There are decades worth of fairly lighthearted, more straightforward superhero fare, so the occasional dip into more mature territory doesn’t bother me. Superheroes are meant to serve as inspiration for us, but sometimes there are instances where there is no black or white and no clear ideal to uphold. In a post-9/11 world where the control of information has been a heavily discussed and used topic in literature, this felt very much like a superhero answer to that. How far is too far in the pursuit of security and safety? There are no easy answers to that question, and Meltzer doesn’t present any. Besides, while the story positioned a certain character as a serial killer and left the rape of Sue Dibny in continuity, it’s not like the series marked the beginning of rape and murder being used as a frequent plot device in the DCU. If anything, it left mindwiping as the most pertinent plot device, something that would feel right at home in the Silver Age.

Greg: That mindwiping will serve as the crux of the next bit of controversy we’ll discuss. As for the question at hand, as you said, there’s no easy answer here. For those with passionate attachments to Ralph and Sue, I could imagine the story being a perversion of the characters they loved. For a modern reader just getting back into comics at the time, however, the presence of these more adult-oriented themes served as another defibrillator that helped jumpstart my passion for the medium again.

Much in the same way Watchmen worked on a lot of levels, “Identity Crisis” took these larger-than-life characters that historically represented moral absolutes and took the long “Marvelization” of them to a new level. By seeing how these heroes and villains react to all-too-normal tragedies, we see these gods turned into humans before our eyes. It also amped up the stakes of the DCU. After so many deaths and resurrections, so many recycled plots, this plowed some genuinely new material and took some major risks. Did it tip the pendulum in DC too far? I’d argue no, because this story can’t be held responsible for the at-times unrelentingly dark works that would follow in later years.

What did you make of the mindwiping itself? Before we address what side WE are respectively on, did you buy the decision in the first place? Did it ring true, in your eyes, for these iconic heroes to make such a decision, given the context?

Nick: In the case of Doctor Light, yes, I bought it. He knew when and where to find Sue and many other loved ones after infiltrating the Watchtower, so it makes sense that the heroes would need to take a drastic measure. However, the subsequent mindwipes that they copped to didn’t really seem to fit. Perhaps there were similar circumstances for each one, but none of those details were offered in the text. Then there’s the big mindwipe. While I actually like the story and the numerous plot threads it opened up, I can’t say I find the rationale for mindwiping Batman to be believable. All of the controversial decisions stemmed from the Dr. Light incident and a desire to protect those closest to the League. While Batman could have opposed the decision or left the League, there’s nothing he could have done to reverse the damage done to Dr. Light or to stop the other Leaguers from continuing to take such measures. Thus, I can’t really see the need for the “inner circle” to mindwipe Bruce. Gotta say I’m glad they did, though, because mid-to-late 2000s ultra-paranoid Bruce is one of my favorite interpretations of the character.

Greg: Well, he may not have been able to physically stop them (yet) or undo their handiwork, but he certainly had the ability to publicize their deeds. Theoretically, he could’ve turned the public at large against the league, or taken measures of his own to strike back at them. Perhaps they feared the depth of his retribution for what he undoubtedly viewed as a gross abuse of power.

Nick: Perhaps, but I still feel like the decision to mindwipe Bruce stems from self-preservation, rather than the preservation of those held dear, which was the entire point of the exercise in the first place. The heroes have all been distrusted by some portion of the public at some point, so I don’t think Bruce going public would have been THAT big of a consideration. Plus, I don’t know that a pre-Batman, Inc., Bruce would have been so willing to expose the league to the public. He would have known that rather than just disgracing the parties involved, he would have been disgracing all the League by association, including heroes he still respected at the time, such as Superman.

Greg: Of all the characters that agreed to that particular wipe, I think Barry was the one that was most surprising.

Nick: I agree, but I feel like that was done more as a way to shake Wally than it was to actually serve as a representation of what Barry was all about. To be honest, I have a hard time buying that Barry would have gone that way. Hal I could see and understand, but Barry felt like a bit of a stretch for me.

Greg: Now, to an ethical question of our own: which side of the argument do you fall on? In the same position as the JLA, would you have gone through with erasing the memories of Light and Batman, and changing Light’s entire personality?

Nick: As someone who is married and is soon to be a father, there are no lengths to which I wouldn’t go to protect my family and loved ones. Perhaps my answer would have been different when I was younger, but at this time in my life, I’m firmly on the side of the mindwipers. Mindwiping a friend like Batman would have been a tougher decision, but I suppose once you’ve gone down that rabbit hole, you have a responsibility to protect your fellow co-conspirators.

Greg: It’s a really interesting conundrum. Morally, every inclination I have leans toward Batman’s side. Invading someone’s mind and stealing their own history? That’s rough.

Yet from my initial reading through today, I find myself siding with the likes of Barry and Hawkman. Dr. Light makes it clear that he knows their identities and will stop at nothing to ruin their lives and, more importantly, the lives of their family and friends. In their position, I’d have made the same decision.

What it harder for me to justify, however, is artificially altering Light’s (and, presumably, other villains’) personalities. That’s a level of invasion and “playing God” that opens up so many cans of worms, it completely flips the definition of “hero” and “villain. That, to me, was a step too far that had more to do with convenience than necessity.

Before we get to our final analysis, let’s talk about some of the negatives in the story.

It’s one of my favorite comic book mystery stories of all time, so I won’t have much to offer here, except that a couple of the characterizations (Barry, for instance, even given the time frame established in the book) were a tad off. Was there anything that didn’t work for you, outside what we’ve discussed already?

Nick: While the mindwipe of Batman plays a major role in the book, it’s a plot that isn’t immediately resolved. That particular plot thread would be addressed later during the lead-in to Infinite Crisis and in the pages of JLA. So, if you’re reading Identity Crisis as a standalone story, it does feel a bit incomplete in that regard.

Greg: That’s a good point. I felt the mindwipe was clearly a background issue designed to be the backbone of future stories, while the main story being addressed here was the murder mystery. I looked at it as a standalone murder mystery but a chapter of an ongoing superhero tale.

Do you feel, if you hadn’t already read most of the follow-up (“Infinite Crisis,” “Crisis of Conscience” and “One Year Later”), that you’d have left the book somewhat frustrated?

Nick: It’s hard to say. I might felt a bit frustrated, but I likely would have been interested enough by the Batman storyline to seek out the continuation of that and see where it went in the end. Even as someone who knew that it was coming before I read Identity Crisis, it still was just as intriguing to me as it was when I first heard of the concept.

Greg: That’s good to hear, as the book had a similar effect on me, even though I read it after the events of Infinite Crisis.

But now it’s time … for our final thoughts.

This stands, a decade after publication, as a powerful piece of superhero crime fiction with just enough supernatural stuff going on in the background. Meltzer and Morales crafted a tense, emotionally gripping thriller throughout, and while the Justice League subplot, and the graphic material, will be debated for years, the book still works for me as well as it did in my initial read-through. It certainly evoked strong feelings from me throughout, which is the point of art, in the end. And it did so while only serving to further the human element that initially drew me to some of my favorite characters. I’d recommend the book to any reader over the age of 15 or so that is interested in seeing a different side of superhero stories. Those more fond of Vertigo titles would probably enjoy this one.

Your thoughts, Mr. Duke?

Nick: My praise isn’t quite as high as yours, but I still enjoyed the story very much. Like you, I’d recommend it to those more mature readers or those whose tastes tend to lean more toward the Vertigo or independent-style stories. For those DC fans who may have read some of the stories of the last decade, especially Infinite Crisis and the subsequent One Year Later stories, Identity Crisis should be considered required reading, as it essentially set the stage for one of the best universe-wide comic events the medium has ever seen. Plus, there are only so many times you can see a hero be put in a situation where you know exactly how they’ll respond. This story makes characters take controversial stands and it puts those characters in places where even long-time fans may be surprised by the direction the story takes.

Greg: And with that, we bring to an end this edition of The Longbook Hunters. If “Identity Crisis” sounds like something you’re interested in reading, be sure to check out your local comic shop, library or website of choice and give it a read. It’s certainly not for everyone.

As always, your feedback is welcome. You can hit us up on Facebook, Twitter (@gphillips8652 and @nickduke87) or through our Place to Be Nation email accounts, GregP@placetobenation.com and NickD@placetobenation.com. Your feedback could be used in a future column!

Next month, we’ll be taking a special in-depth look at the autobiography of Air Wolf star Jan Michael Vincent.

Oh, and we might also talk about The Ultimates 2 by Mark Millar and Bryan Hitch.

Nick: Or maybe not. You never know.

Greg: The only thing that’s for sure about the Hard-Traveling Fanboys is that nothing’s for sure.

Nick: Just when you think you have all the answers, we change the questions!