Three of college basketball’s greatest coaches will be inducted on September 8 along with Gary Payton and Bernard King

As a fan of the Southeastern Conference and lifelong LSU Tigers fan, it is important for me to point out that when it came to basketball as a kid, my heart was not in Baton Rouge but in Lexington a few states north. Even in the midst of the Shaq Attack before he left LSU for the NBA in 1992, I was always a Kentucky Wildcats basketball fan first. It was in ‘92 that I watched in agony as Duke’s Christian Laettner sank a buzzer beater over Kentucky in what you could easily consider the greatest game in college basketball history. A year later, with Laettner gone, Kentucky coasted to the Final Four in the Superdome, which was a 30 minute drive from my house. I was so excited that I even bought a shirt for that Final Four in hopes of seeing my two favorite programs, Kentucky and North Carolina, face off for the national title. But in another great tournament game, Kentucky was ousted in overtime by the Fab Five of Michigan. I was so mad at Michigan that I was the only kid on the schoolyard who actually wanted the Fab Five to lose to the Tar Heels, and was redeemed in shocking fashion when Chris Webber made that ill-fated timeout, costing his team the chance to win.

Then in 1996, it all came together for the Wildcats in the NCAA Tournament. What sets the 1992 team apart for many Kentucky fans is not just the fact that they almost ousted a magnificent Duke team in that great game. They had just finished a two-year postseason ban due to recruiting violations under previous head coach Eddie Sutton, and outside of Jamaal Mashburn, there were no pro players on the Kentucky bench. That year’s team has been nicknamed as the Unforgettables by Kentucky fans, and the four seniors on that team, in an unprecedented move, all had their numbers retired. The 1996 team, however, put the finishing touches on the excellence that team established once more for the Wildcats, and they did it with a dominant swagger. Every fan of college hoops loves a super team, and the ’96 Wildcats were just that, nicknamed the Untouchables by locals and consisting of 11 players who went on to play in the NBA.

I will never forget watching with my dad, LSU born and bred, one of the most utter dominations of another team we had ever seen at the hands of that very team in Baton Rouge. Dale Brown is a favorite of mine, but the various defensive traps and disciplined shooting display that Kentucky educated the lowly Tigers with in that game was a sight to behold. Antoine Walker, Tony Delk, Walter McCarty, Derek Anderson, and Ron Mercer playing team basketball against college kids? Forget about it! That team went on to lose only two games and win the national title against Syracuse. They were so good that the next two Kentucky teams, who were far worse than the ’96 version, were one win away from clinching a championship three-peat, not done in college basketball since John Wooden days at UCLA. The ’96 Wildcats were my favorite team ever and I admired the fighting spirit of the scrappy ’92 team. Both teams had only one common thread: They were both coached by Rick Pitino.

It is amazing to think that the wide-eyed mastermind of these legendary teams in SEC country was a well-dressed New Yorker who played at UMass and got his first break in coaching as an assistant at the University of Hawaii back in the late 1970’s. After a stint there, he was an assistant to a newly hired head coach at Syracuse named Jim Boeheim. He eventually took the head coaching job at Boston University and gave them their first NCAA Tournament appearance in 24 years. He then became an assistant coach for Hubie Brown with the New York Knicks in the early 80’s before taking the head job at Providence College in 1985. It was at Providence that Pitino first showed his forward-thinking skills as a college coach as he installed a full court press while embracing the newly made three-point line. While traditionalists like Bobby Knight sniped about how the three-pointer was bad for the sport, Pitino turned a scrawny buzz-cut-wearing guard named Billy Donovan into Billy the Kid, a silent killer from the outside. Not too long after his six-month-old son died from congenial heart failure, Pitino led Providence on an unlikely run to the Final Four in 1987 where he lost to his former Syracuse boss Boeheim.

At 35 years old, Pitino was lobbied as the next coaching wunderkind and was quickly hired by the Knicks, this time as the head coach. He produced two postseason runs in New York before taking the Kentucky job, which is one of the most coveted and nitpicked positions in all of sports. Even under the stress of delivering yearly greatness for fans who were accustomed to success, Pitino delivered and then some as he brought the title back to Lexington in ’96 and came within five minutes of another title in ’97. The NBA would come calling again, and although leaving Kentucky was the toughest thing Pitino ever did (in his own words), the Boston Celtics offered Pitino full control of the organization and a record-setting salary to go with it. Pitino took the risk and paid dearly for it. After losing out on the Tim Duncan draft lottery, he failed to find the right touch in Boston, finishing under .500 each season and providing a depressingly quotable meltdown back in 2000. Celtics fans still shudder at the very mention of Pitino’s name today. A year after that tirade, Pitino was gone from the NBA, never to return.

By the time Rick Pitino was available to return to college coaching again, this time once and for all, the kingdom he had helped build in Kentucky was already run by Tubby Smith, who had recently won a national title mostly with Pitino’s players. Instead, the legend replaced another legend in Denny Crum at the University of Louisville. The sense of betrayal for Kentucky fans for Pitino to coach the stateside rivals had the same vitriol as it did when Nick Saban left LSU for the Miami Dolphins only to go back to college as the head coach of Alabama. A rivalry that was always hot was now nuclear as the yearly Kentucky/Louisville matchup became one of the most anticipated games of the season. As the years rolled by, the former hot commodity in coaching had become an institution in college hoops as he led Louisville to similar success as he had in Kentucky. Before 2013, Pitino led the Cardinals to two Final Four and two Elite Eight appearances and is the second coach to lead three different teams to the Final Four (John Calipari, unofficially due to sanctions, is the other). His team’s win over Michigan in the 2013 national title game made Pitino the only coach in college basketball history to win the national championship at two different schools. A few days earlier, he found out he was being inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame.

Although I remain a loyal Kentucky fan and fervently support the pro-ready system that John Calipari, a longtime rival of Pitino’s, has built in Lexington, I cannot help but cheer for Slick Rick to keep on winning when I see his games. Clearly, he doesn’t need my support, anyway. He will soon have led Louisville through four different conferences (Conference USA, Big East, American Athletic, and ACC) and he is likely to win a conference title at each stop. That goes without mentioning his many SEC titles while at Kentucky. With one more win, he will pass Wooden himself in career victories. His coaching tree is almost as vast as any other in the game, with the likes of Donovan, Travis Ford, Herb Sendek and even his son Richard taking head coaching positions. He has had some incredible lineups like the ’96 Kentucky and ’13 Louisville squads that won it all, but he has also found a way to use cerebral coaching skills to get the most out of teams that really did not have a lot to offer. Pitino coaches his team into a creative, crafty whole that meant far more than the sum of its parts, probably better than any coach in the last two or three decades. More than 20 years after first falling in love with basketball when Pitino and Mike Krzyzewski did battle in that great game, it is incredible to realize that the two coaches who best represent college basketball greatness after Wooden and Knight are the same two coaches today, who will soon face off in the same conference starting in 2015. Krzyzewski sealed his place in basketball lore when he coached Team USA to Olympic gold in Beijing and London. Pitino will officially join him in coaching royalty this weekend.

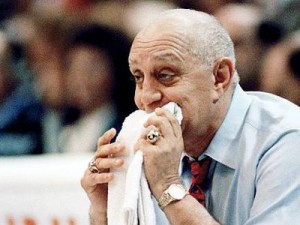

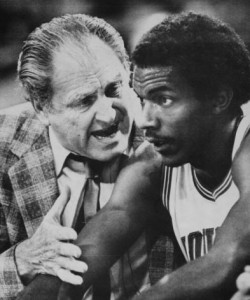

While Pitino’s sleek businessman-like approach would make him more likely to place a towel on his seat to keep it warm, Jerry Tarkanian would bite nervously into his towel during his coaching days. Even in an enterprise as wild and out as college sports, no coach was more distinct of a character than “Tark the Shark.” If you saw him from the bench chewing on cloth and staring at the floor in a frantic pose, you would have thought he was an overzealous fan who was sitting in the wrong seat. You could tell by his demeanor that Tarkanian’s basketball career came from unlikely origins. He was the son of Armenian immigrants in Euclid, Ohio, and played for a couple of years at Fresno State University. He earned his licks coaching at the high school level before coaching at two junior colleges in California. He wound up winning four junior college championships with a .891 winning percentage, which is still a junior college record. He moved on in 1968 to Long Beach State, where he recruited gems like Ed Ratleff and went 122-20. The reason nobody remembers this is because back then, the NCAA Tournament kept the schools in their regional brackets and the 49ers could never beat Wooden’s UCLA teams to get to the Final Four.

Unfortunately, if you track Tarkanian’s history in college hoops, the sleuthing and suspicious NCAA was not far behind as they hammered Long Beach State with violations right after Tark had left to take the head coaching job at a newly minted Division I school called UNLV. Unlike many coaches, however, Tarkanian was combative and defiant with the NCAA’s rulings and challenged them at every turn. When they tried to suspend him for two years back in 1976 for “questionable practices,” Tark brought it to a Nevada court and got it thrown out (That case went all the way to Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of the NCAA many years later). Tarkanian would go on to lead that 1976-77 UNLV team, nicknamed the “Hardway Eight,” to a 29-3 record and his first Final Four. Not only was Jerry bringing in loads of talent to UNLV, but he renamed the team the Runnin’ Rebels, changing the culture of the school from an afterthought to a basketball mecca.

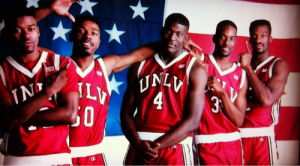

Like Tarkanian’s odds with the NCAA, his Runnin’ Rebels were never afraid to stray from the norm on the court and, like Pitino’s Providence Friars, fully embraced the three-point shot in 1987. It resulted in a Final Four appearance for a UNLV team (featuring studs like the late Armen Gilliam, Freddie Banks, Jarvis Basnight, and Eldridge Hudson) that lost only three games all year. The third loss, however, was a semi-final loss to eventual champion Indiana in a game where Banks made 10 three’s, which remains a Final Four record. But for Tarkanian, the third trip to the Final Four at Denver in 1990 would definitely be the charm. It was that season that the Shark put together one of the most exciting, free-wheeling, and (in some cases) despised teams in college basketball history as the Rebels surmounted a squad of high flyers like Larry Johnson, Greg Anthony, Stacey Augmon, and Anderson Hunt. While Pitino liked to implement frantic, chaos-causing defense for many of his teams, Tarkanian unleashed similar puzzlement with the amoeba defense and a potent fast break to go with this assortment of pros. The results were spectacular. They finished with a 35-5 record and were the only team to score over 100 points in a national title game as they dismantled Duke 103-73 for Tark’s first and only title.

The scary thing about the gaudy highlights from the 1990 squad is the fact that the following year’s team was even more dominant. Larry Johnson won the Wooden Award and would later be the #1 overall pick in the NBA Draft while Augmon, Anthony, Hunt, and George Ackles went a blistering 34-0 going into their Final Four rematch with Duke. UNLV seemed on the cusp of becoming the team that would replace the 1976 Hoosiers as the last undefeated national champion in college hoops history, but the tables were turned. One year after losing by 30 to the Rebels and one year before his game-winner over Pitino’s Wildcats, Christian Laettner helped carry the Blue Devils to a stunning 79-77 upset over the undefeated Runnin’ Rebels. Although Laettner, Grant Hill, and Bobby Hurley were always respected as a terrific team leading up to that win and went on to win back-to-back titles, the focus was more on UNLV’s shocking fall after two years of utter dominance in the sport.

With that fall came a fatal fallout for the Rebels as earlier that season, a new NCAA investigation discovered the UNLV program being directly linked to a gambling bigwig named Richard Perry, also known as “Richie the Fixer.” An infamous photo from 1989 revealed Perry in a hot tub with three UNLV players after Tarkanian had been reportedly told to keep Perry away from the team. The NCAA initially ruled that UNLV would be banned from the 1991 tournament, but a compromise was made where the team could defend its title but would be banned from the 1992 tournament. After the hot tub photo leaked to the newspapers, the school had seen enough of Tark’s tumultuous tenure at UNLV and forced him to quit after the ’92 season was over.

After 19 glorious but controversial years coaching at UNLV, Tarkanian made a pit stop as an interim coach for the San Antonio Spurs, but he had even less success in the pros than Pitino did. After going 9-11 in ’92, Tark was quickly fired but used to his contract settlement money to sue the NCAA for what he deemed as a lifelong witch hunt and a series of wrongful investigations. He returned to his alma mater at Fresno State in 1995 and, like in his Long Beach State days, brought in a lot of junior college recruits and, like in his UNLV days, talented players with sketchy histories like Rafer Alston, Chris Herrin, and Courtney Alexander. Tarkanian won at least 20 games in every season he coached there outside of one, but the teams were not as talented overall and they never went any farther than the second round. Along with the marginal success was the trouble that followed him at other schools. If there was one weakness in Tarkanian’s career, it was the willingness to give troubled youth a second chance to make good at his program. Unfortunately, that generosity backfired on Tark many times, and the NCAA was more than ready to hand down punishment for those mistakes. Along with player arrests (including one involving samurai swords) came discoveries of improper benefits and academic insufficiencies. By the time the case was closed, 49 of Tark’s 153 wins were vacated.

After retiring with some residual shame from Fresno State in 2002, Tarkanian has written books and reveled in his unique celebrity status in Las Vegas. Not only has he won nearly 1,000 games as a coach on every level, but he has coached 44 players who have gone on to the NBA. He is fifth all-time in winning percentage at .781 and got his team to the Sweet Sixteen 13 times. He also got the last laugh on the NCAA as his harassment lawsuit against them led to a settlement in 1998 for over $2.5 million, an unprecedented payout by the organization. I am thankful that at age 83 and with a newly installed pacemaker, Tarkanian will be alive to witness his induction in Springfield in a class of coaches that, despite his questionable history, he deserves to be part of. It was only fitting that just recently the Thomas and Mack Center, where UNLV plays basketball, unveiled a beautiful statue immortalizing Jerry Tarkanian, as he nervously sits down chewing on his towel in perpetuity.

While Pitino had his awesome Kentucky group in ’96 and Tarkanian unleashed the dominant Runnin’ Rebels in ’90 and ’91, Guy Lewis had already retired after leading a couple of super teams of his own, all with the Houston Cougars. His first elite squad was back in the late 1960’s when Lewis pioneered racial integration and brought in the first two African American players in the school history. Those two Louisianan recruits were a future Hall of Famer in Elvin Hayes and another NBA veteran in Don Chaney. Not too shabby. Nicknamed the “Big E,” Hayes led the Cougars to an epic January 1968 matchup against Wooden’s UCLA Bruins led by another big man in Lew Alcindor. UCLA had won 47 games in a row and the contest was so big that that it was put in the newly built Astrodome and became the first ever regular season college basketball game to air on national television. It was called the Game of the Century, and the hype was certainly met. In front of over 55,000 fans, Hayes had 39 points and 15 rebounds against an injured Alcindor as the Cougars ended the Bruins’ two and a half year undefeated streak with a 71-69 victory. Without that televised game, the television popularity of “March Madness” may have never been realized and ultimately ignored by TV execs.

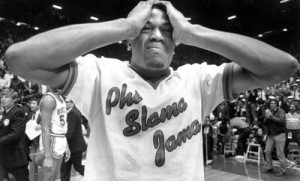

Unfortunately for Lewis, Houston had to rematch UCLA in the Final Four later that season, and it went the other way as the Bruins clocked the Cougars 101-69 on their way to another national title. Even after Hayes and Chaney graduated, Lewis went to coach top talents like Otis Birdsong, Dwight Jones, and former Globetrotter “Sweet” Lou Dunbar to consecutive 20-win seasons at Houston. But it was in the early 80’s that Lewis and his alma mater were back on the national radar with one of the most exciting teams ever put together in college hoops: Phi Slamma Jamma. With two future Hall of Famers in Clyde Drexler and Hakeem Olajuwon leading the way, Lewis’ team gladly adopted a scintillating up-and-down pace that was big on athleticism and, most notably, dunking. Throw in really good college players like Michael Young, Benny Anders, and Larry Micheaux, and you’ve got yourself a doozy of a team. Phi Slamma Jamma became so popular in the media rounds that the starters got their own nicknames. Hakeem was the Dream, Clyde was the Glide, Micheaux was Mr. Mean, Young was the Silent Assassin, and Anders was hilariously dubbed the Bomber from Bernice.

After finding their groove and losing to Michael Jordan’s North Carolina team in the Final Four in the Superdome in 1982, Houston had a phenomenal 1983 season, losing only one regular season game and going into the championship game on a 26-game winning streak. They did not just defeat their opponents, they would embarrass them with alley oops and throwdowns galore. Drexler’s dunk over Memphis’ Andre Turner in the ’83 tournament is one of the all-timers for me. And in an almost heavenly fate, Phi Slamma Jamma met up in the Final Four in Albuquerque with another high-flying fraternity: The Doctors of Dunk in Louisivlle. The game was highly anticipated and expected to be a display of superb athleticism, and 15 years after Lewis’ Game of the Century victory over UCLA, this one took the cake. It was faster than basketball on roller skates because the players always seemed to be floating effortlessly in the air. After forty minutes of endless, mind-blowing plays, Houston flew past Louisville 94-81 in a memorable victory. It seemed like the poor Cinderella team on the other side, North Carolina State, would meet their demise at the hands of the Dream and the Glide in the title game. But the basketball gods had a different plan in mind.

Early in the national championship game against NC State, Drexler got into major foul trouble and the frenetic style of the Cougars had to be abandoned in order to regain the lead. Unlike Tarkanian, who would nibble on his towel as his teams ran amok, the southerner Lewis would tightly grip his checkered towel as he installed a slow down tempo in the second half in order to limit NC State’s possessions and eventually tie the game. I think we all know how that ended. Lorenzo Charles’ magical basket put an end to Phi Slamma Jamma and Lewis’ title hopes with, of all things, a dunk. As joyous as it was to remember Jim Valvano looking for somebody to hug after one of the biggest upsets in the history of sports, it was painful to see Lewis get so close to getting the trophy he had coached decades for and just fall short.

Although Lewis will forever be remembered by casual fans for the 1983 Houston team, the Cougars were almost as good the following season without Drexler and Micheaux as they played a more Hakeem-centric half-court game to lower scores all the way to the 1984 national title game in Seattle. It was there, however, that Lewis’ last chance at a title went awry as Olajuwon met another future Hall of Fame center in Patrick Ewing and the Georgetown Hoyas. Georgetown would beat Houston convincingly in the battle of the big man, and Lewis would retire two years later from Houston. He finished with nearly 600 wins and a lasting legacy at the University of Houston living quarters, where he has lived since 1959. It’s pretty easy to see why the school named their court after him. Among the three college legends being honored this weekend, Lewis was not only considered the more traditional coach but also the one who did not win a national championship. Although 30 years of coaching at Houston left his hands empty for the ultimate prize, being inducted along with colleagues like Pitino and Tarkanian is not a bad consolation prize.

I grew up watching college basketball years after Lewis had already stepped aside and in the aftermath of Jerry Tarkanian’s run with the Runnin’ Rebels, while Rick Pitino was the crown prince of the SEC. But as you back track the great teams and coaches that helped shape college basketball, you have to admire Guy Lewis’ impact at Houston in the 60’s and 80’s and the unconventional nature with which Tarkanian re-established West Coast basketball after John Wooden retired. Even though he is now a Benedict Arnold in the eyes of Kentucky fans like myself, Pitino will always be my guy and remembered by many as the most accomplished of the three coaches. With that said, I am glad that all three men are going to get the call to basketball immortality together.

Although I focused the majority of my time to honor three college coaches that I dearly admire in this upcoming Naismith Hall of Fame ceremony, I have to also mention some of the other players, coaches, and ambassadors for the game who will also be granted induction alongside Pitino, Tarkanian, and Lewis.

GARY PAYTON

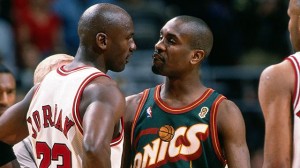

Along with Guy Lewis and Jerry Tarkanian, another coaching legend back in the 1960’s, 70’s, and 80’s was the late Ralph Miller, who spent many years coaching at Oregon State. He retired in 1989, but may have saved his greatest player for last when he recruited Payton to Corvallis. A point guard out of Oakland, Payton cut his teeth as a kid with a neighborhood buddy and future Hall of Fame point guard named Jason Kidd. He spent four years at Oregon State where he became (at the time) the school’s career leader in points, field goals, assists, and steals. He was selected second overall by the Seattle Sonics in 1990 and he never looked back. He got the nickname The Glove because of his brilliant stranglehold defense on other guards. If you look at the stats for Michael Jordan in the 1996 NBA Finals when Payton primarily guarded him, you can see that Payton earned that defensive respect.

But make no mistake: Payton had a lot of offensive skills to go with that bulldog reputation. He is 21st all-time in points scored along with being 7th in career assists. His main man on the other end of his passes was the freakish Shawn Kemp, with whom Payton enjoyed his most prominent success under head coach George Karl. Unbelievably, in his entire career, Payton only missed 25 games total, ranks 7th all-time in games played, and at one point played in 300 straight games. He was a nine-time All-NBA Defense First Teamer and remains the only true point guard to win Defensive Player of the Year back in ‘96. He even won two Olympic gold medals. And with all that game, he had a lot of trash talk to go with it. The deadly serious Kobe Bryant considers Payton the funniest teammate he ever had along with Shaq. He is third all-time in technical fouls behind Rasheed Wallace and Jerry Sloan, and his outspoken personality led him to hilarious interviews, rap songs, and weird Nike commercials like this.

After a quick stop in Milwaukee, Payton brought his smooth offensive game and verbal leadership to Los Angeles in hopes of winning that elusive ring along with Karl Malone. But after losing to the Detroit Pistons in the 2004 Finals, he was on the move again before winding up with Shaq again, this time with the Miami Heat. He was more of a role player in 2006 in Miami but was a key part of winning his first and only NBA title as he hit two clutch shots against the Mavericks in that series. A year after getting that ring, Payton walked away from the game, but continues to exhibit his verbal skills as an analyst for newly launched Fox Sports One. Payton was also a strong voice in support of keeping the Sonics in Seattle before Clay Bennett and David Stern relocated the team to Oklahoma City. Thankfully, the banner for Gary Payton’s retired No. 20 remains in Seattle as he was probably the greatest player the Sonics ever had.

BERNARD KING

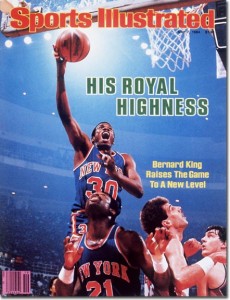

For some younger fans who stumble on this great 80’s Converse commercial, the first reaction for many of them probably is, “Who is that dude in the Knicks uniform?” I have to admit that I grew up watching barely anything that Bernard King did in the NBA, but his accomplishments before injuries cut him down were the stuff of legend. King was straight out of Brooklyn but wound up playing at the University of Tennessee where he and Ernie Grunfeld teamed up to make the Ernie and Bernie Show. King would be awarded SEC Player of the Year three years in a row and was drafted by the New York Nets in 1977. He bounced around from the Nets to the Jazz to the Warriors before finding his calling back home with the New York Knicks in the early 80’s.

Although he was 6’7” and played small forward, King reminded me a lot of a younger Amare Stoudemire at the power forward position as he was much quicker and more explosive at his position than anyone else and had a tremendous knack for scoring inside and out. He scored 50 points in back-to-back games and is one of only twenty players in NBA history to score 60 points in a game, which he did on Christmas Day of 1984 against the Nets. At that point, King was a three-time All-Star, selected to the All-NBA First Team two years in a row, was the league’s scoring champion, and averaged 34.8 points per game in the 1984 playoffs. He went seven games with Larry Bird’s Celtics and had an all-time performance against Isiah Thomas and the Pistons in one of the best games in league history.

Unfortunately, the superb play of Larry Bird and Magic Johnson buried King’s notable headlines in his prime before he suffered a torn right ACL against the Kings in March of 1985. Like Stoudemire’s fated stint as a Knick, the knee operation was serious and he missed the entire 1985-86 season to get back. He returned without the explosiveness and lateral movement that made him such a dangerous scorer, and by the end of the 1987 season, the Knicks cut him. He made the most out of a later stint with the Washington Bullets, even making the All-Star team in 1991, but after taking another year off and trying another comeback with the Nets, King officially retired in 1993.

Unlike Payton, whose durability and consistent numbers made him an easy choice on the first try for the Hall of Fame, King had to sweat out his eventual induction years after he had walked away because he had a much smaller number of games played compared to other all-timers. Even with that sampling, though, King is still 41st all-time in points scored. His Paul Bunyan-like status as an unstoppable forward as the NBA’s popularity grew in the early 80’s will help Number 50 finally get to rap his way to the Hall of Fame. I just wish that fate was kinder to King so that this induction would have happened years earlier.

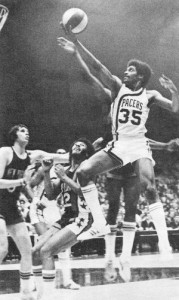

FROM THE ABA COMMITTEE- ROGER BROWN

A solid, taller utility guard who got little notoriety because he was banned by the NCAA and the NBA in the 60’s for his involvement in the Connie Hawkins scandal. So he played in the ABA, where he was the Indiana Pacers’ first ever signing. Brown helped the Pacers win three ABA Championships while scoring 53 points in an ABA Finals game. He never played in the NBA even though he was eventually reinstated. He also had his No. 35 jersey retired by the Pacers organization. Brown passed away after a bout with cancer in 1997.

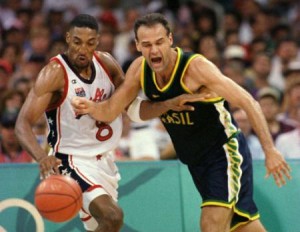

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE- OSCAR SCHMIDT

When fans of international basketball talk about the all-time greats from their native countries, one of the first names has to be Oscar Schmidt from Brazil. Legend has it that after tallying all his numbers, the 6’8” forward with frightening shooting skills holds the all-time record in points at close to 50,000. He is already in the FIBA Hall of Fame and had the longest tenure as an active player than anyone else, playing from 1974 to 2003 without a break. He led Brazil to in 38 Olympic contests and helped them win the Pan Am Games in 1987 against Team USA. Here he is scoring 46 points against the Americans in the gold medal game. Drazen Petrovic is still considered by many as the best foreign jump shooter in that era, but Schmidt was right behind him.

OTHER INDUCTEES: RICH GUERIN (Veterans Committee), DAWN STALEY (Women’s Committee), SYLVIA HATCHELL (Women’s Committee), DR. E.B. HENDERSON (Early African American Pioneers Committee), RUSS GRANIK (Contributor Direct Election Committee)