Mild-mannered reporters by day, Greg Phillips and Nick Duke share an intense love of comic books that has made them the Hard Traveling Fanboys. Over the course of their travels through comicdom, they have encountered numerous stories through the wonder of trade paperbacks and graphic novels. Once a month, Nick and Greg will review one of those collections in The Longbook Hunters.

Nick: Welcome to the latest edition of The Longbook Hunters, a monthly series in which Greg and I dust off one of our old trade paperbacks or hardbacks and give it a read before sharing our thoughts on it with you.

Typically, we’re going to tackle books that one of us has read, but the other has not. Last month, I read the first volume of Y: The Last Man for the first time. This month, we’re sticking with the alphabet theme as we’re going to get Greg’s thoughts on his first ever reading of V For Vendetta.

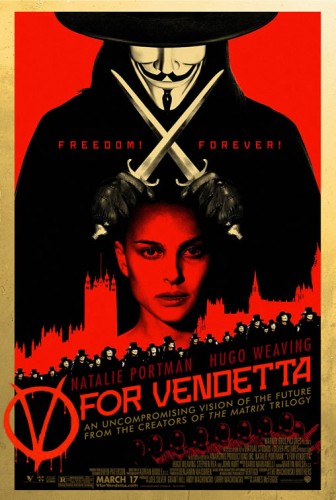

Greg: I feel like I need to turn in my geek card for having not read this book before, but I just never got around to it. My first exposure to “V” was through the 2005 Wachowski Brothers-penned film based on the book.

Nick: I first was introduced to V through the theatrical version from several years back, and it wasn’t until 2010 that I gave it my first reading.

Did you feel like the movie shaped your expectations going into the book?

Greg: In some ways. I knew the basic overarching theme was the same, but I also knew there were some major changes to characters and story elements, so I knew to expect a different experience. The characters from the movie definitely led to my preconceived thoughts of them going into the book, though.

Nick: OK, so the book throws you right in, as you meet the two main characters, Evey and V on pages 1 and 2, respectively. The opening pages are similar to the movie’s opening scene, though with a major change in the form of Evey trying to solicit men to pay her for sex. What were your thoughts a few pages in?

Greg: The first few pages of the book are almost identical to the opening moments of the film, so I wasn’t too taken aback. The biggest change this early was seeing that Evey is younger and less intelligent than Natalie Portman’s character, and, of course, the prostitution angle. I could tell early on that the book would treat its characters much more harshly than did the film, and I was excited to see what Moore would do with the rather condensed panel layouts.

V also comes off as less charming and more creepy in his initial appearance.

Nick: That is one thing that definitely stood out to me about the book. It’s already a dense read, made even moreso by the more tightly arranged layouts. It made the experience more similar to reading a prose novel for me. Was that intimidating at all as you started to delve into the work?

Greg: Surprisingly, no. It did feel different from my normal comic-reading experience, though. There were times it felt like reading a traditional novel, simply in terms of how dense the material was. But honestly, I became immersed so quickly in the world Moore and Lloyd were crafting that I breezed through the book. I actually felt Watchmen was more intimidating when I first began reading it.

Nick: That brings me to my next point. As the story opens, it is clear that the world the story takes place in is not one we are familiar with, yet Moore and Lloyd spend a lot of time building that world and allowing you to understand the plight of both the people and those in power. Your thoughts on the alternate version of the 1990s that Evey and V exist in?

Greg: Dystopian futures aren’t exactly unusual in the world of comics, but they usually aren’t as detailed or fully realized as the world of V for Vendetta. When the book was written, the late 1990s were still the better part of two decades away. While films like The Terminator featured a world ruled by artificial intelligence, the technology presented in V is oddly prescient. Security cameras exist everywhere, as does audio surveillance equipment. The parallels with George Orwell’s “Nineteen Eighty-Four” are obvious and intentional, but Moore and Lloyd focus as much on the lives of the oppressors as those of the oppressed. The dichotomy is established early between the people in power like Adam Susan and the dregs of society like Evey Hammond, but most fascinating to me were the people caught in the middle. Eric Finch and Rosemary Almond represent the average middle-class citizen who knows things are wrong but are too afraid or comfortable to create any change.

The perils of political extremism and the power of fear have rarely been as well explored as they are here.

Nick: Finch is perhaps the most relatable character in the novel, but we’ll get to him in time. Obviously, any discussion of the characters that inhabit this world must start with Evey Hammond. As you mentioned, she isn’t the most intelligent girl, nor is she stupid by any measure. I think I’d best describe her as naive more than anything else, something that V is able to exploit to a certain degree. What were your feelings on Evey and the journey she takes through the book?

Greg: The book clearly intends to create a level of empathy with Evey, and it definitely succeeded with me. I truly felt for her from the very beginning, and as it becomes clear that V is toying with her, that level of empathy only grows. She’s someone who, by no fault of her own, has been a smear on the windshield of life since a young age. And it seems everyone around her, save Gordon, uses her for their own purposes. Whether it’s the Fingermen abusing her physically or V himself torturing her psychologically, she goes through more than anyone should be expected to endure.

And yet there’s a strong argument that she comes out a better person. She holds onto her convictions — even in the end, she refuses to kill for V. But she also becomes the symbol that will be used to rebuild society from the ashes of the fascist empire Susan and his Norsefire party had created.

Nick: And that could be one of my few complaints with the book. For a book that exists largely in a world that is believable, the amount of psychological trauma that Evey is able to endure requires a lot of suspension of disbelief.

I do agree, however, that V’s actions towards her become rather reprehensible at times, even though V is supposed to represent an ideal for the people of England. How did you feel about this very savage, very morally ambiguous V?

Greg: Of all the changes from book to film, that was the most extreme. Where V in the film is very much a flawed hero (he still tortures Evey, but he is portrayed as a romantic who feels genuine regret for his actions), here he’s single-minded and hell-bent on achieving his goals at any cost.

There can be no doubt that V’s ultimate goal was heroic — toppling the corrupt government and putting power back in the hands of the oppressed. His methods, however, are entirely questionable, and I’d argue that’s the point. V is the avatar of anarchy (I’m sure Michael Cole will begin using that monicker for a wrestler on Monday Night Raw soon), where Susan is the representative of extreme conservatism. Throughout the book, V only does what is good for him or his cause. Even when he purports to care for Evey, it appears as though his ultimate goal was merely to mold someone in his image.

Still, there can be no doubt that, as morally questionable as V’s actions can be, the actions of those in power are far worse.

Nick: Yes. V and Susan really do represent two very distinct, opposite ends of a spectrum, both of which include violence and intimidation. I feel as if there are some who might read this book and actually empathize with Susan more than V, but that would say more about the reader than the work.

Greg: I think Moore intentionally creates two twisted, deformed people as the representatives of two polar extremes. The most important thing to understand heading into this book is that you, as a reader, have to ask yourself important questions about your own views. This is a book that makes you think, and the answers you find aren’t always comfortable. I actually spent two nights considering whether V’s goals were ultimately worth the torment he put Evey through.

Nick: And, what was your conclusion?

Greg: Heh. After all that consideration, I still haven’t really made up my mind. V’s actions ultimately led to freedom for millions of people and gave them hope for the first time in some of their lifetimes. There is no telling how many lives he saved by demolishing the government and giving the people a symbol of hope.

But the problem with “the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few” is that it really sucks if you’re the few.

I tend to lean towards “worth it,” especially since Evey sees it that way by the end. But it’s a moral dilemma that literally kept me up at night. Lloyd’s artwork during the torture scenes was masterful. It actually did a better, more extreme job of illustrating Evey’s physical decay than did the film.

Nick: Yes, David Lloyd’s art was quite good, even if he wasn’t really given free reign to play with panel layouts. As is the case with most artists that work with Alan Moore, they don’t get quite enough credit for the book’s success and high quality.

As you said, his ability depict emotion was key here, as the book really was more about interpersonal relationships than larger-than-life character designs.

Greg: My only problem with the art was that some of the characters were drawn so similarly to one another that I got them confused. Derek Almond and Dominic often looked so similar that I had to double-check the dialogue, and the female characters have a few moments of looking identical.

Overall, though, the art was tremendous. The emotion was so raw throughout the book that even scenes between two characters I hated managed to draw me in.

Nick: YES! I’m glad I wasn’t the only one who had a hard time keeping up with who was who.

Around V and Evey are a plethora of supporting characters and to address each would take more space than anyone would care to read, so we’ll stick to just a small sampling. Greg, who were your favorite non-V or Evey characters? I think mine were Finch, obviously, Susan because of what a great villain he made and Rose Almond, whose journey is nothing if not heart-wrenching.

Greg: Finch is obviously one of the main characters, but I’d definitely include him. He’s the closest thing to a true everyman in the story, which is astonishing considering that he actually worked with this oppressive government for years.

I actually liked Dominic, Finch’s right-hand man who is another seemingly decent guy stuck in a horrific system. I have to confess that I found any and every scene with Helen Heyer and her neutered husband, Conrad, to be incredibly fascinating. She’s just such a shrewd manipulator, portraying the high-society socialite in public while secretly being every bit as evil and manipulative as Creedy, Susan and the rest of the book’s antagonists.

Rose is another interesting character who goes through the emotional wringer. And when it comes to downright evil characters, it doesn’t get much creepier than Bishop Lilliman.

Nick: Bishop Lilliman’s only fault is that he wasn’t around longer.

Let’s talk about Alan Moore. He’s always had a knack for story and plot, but I was surprised at how much I loved the dialogue in this. You?

Greg: I almost always love Moore’s dialogue, so it didn’t surprise me that it was great here. I think he’s the best writer the comic book industry has ever had, and V is one of the greatest examples of that. Each conversation seems to have a subtext, an underlying layer of venom or intrigue or misdirection.

Nick: There was so much subtext here that it’s one of the few books I remember doing an instant re-read of as soon as I finished my first. Not just to enjoy the story all over again, but to soak up all the detail as well. Very similar to Watchmen in that regard.

Greg: A notable exception, which perhaps comes from my status as an American, was anytime Ally Harper opened his mouth. I could barely make sense of his Scottish accent as it was written.

V is certainly a book I’ll probably be rereading for years.

Nick: OK, all in all, who would you recommend this book to? I can’t say I’d recommend it to new readers, as that would be a bit like throwing a new swimmer into the Pacific Ocean. Too much too soon.

I think it’s perfect for veteran readers looking to branch out from the typical superhero fare the genre has to offer, as well as anyone who has read and enjoyed Watchmen or another Moore work.

Greg: I’d recommend it to anyone who is a fan of classic literature or history, regardless of their past with comics. I’d certainly recommend it to those who have studied the form and have read Moore’s more mainstream superhero fare like his Green Lantern Corps issues or his Swamp Thing run. The real danger would be starting someone off with this or Watchmen, which are among the pinnacles of the medium, simply because of the inevitable quality dropoff when they move to other books, even high-quality ones.

Nick: How do you think it compares to the rest of Moore’s work? I’ve long avoided talking about it publicly, largely because I think I actually prefer V to Watchmen, something that is almost a sin in the eyes of many comic book aficionados.

Greg: It doesn’t match Watchmen for me, but only because I think Watchmen is the ultimate comic book. It does things with the form and structure of comics that V didn’t even attempt, and it’s one of the few books that truly feels as if the artist and the writer are so in-sync that it couldn’t have worked with anyone else in either of their roles. Dave Gibbons played a more integral role to the storytelling process in Watchmen than Lloyd did in V, in my eyes. But that’s no knock on Lloyd or the book. V is tremendous, probably the second best Alan Moore work I’ve read, though it’s really hard to compare Watchmen or V to his mainstream superhero work like Vigilante or Superman.

It’s yet another example of how great the man is at his craft, especially during that era, when he was really hitting a creative stride like no other.

Nick: Last topic we’ll touch on is the film. You actually rewatched it after reading the source material for the first time. I’ll be honest, I liked the movie a lot the first time I saw it. However, after reading the book, I can’t help but wish the movie had stuck a little closer to the novel, mostly in regards to the characterization of V and his actions he took to accomplish his ultimate goal. I think the movie, while still able to maintain a sense of ambiguity, lost a lot of the so-called gray areas that V treaded in. The V of the film was much more romantic and grandiose than the at-times bone-chilling V of the novel. Other than V and the fact that the movie is far less subtle with its themes and plot devices, I still find the movie to be an entertaining film that’s worth a watch every now and then. The book, however, is among my top 10 works in the comic genre.

Greg: I did indeed revisit the movie, which I hadn’t seen in at least four years. I loved it at the time it came out, and I worried I’d feel the same way you do after having read the book. To my surprise, I still loved it. I actually found some of the changes the Wachowskis and James McTeigue made to be perfect for the film. For instance, making Gordon both a more prominent character and a closeted gay man served to help both the theme of the story and provided some excellent scenes with Evey. I also liked the way the film modernized things and built Eric Finch from the ground up as a true hero.

On the downside, the film is much more heavy handed with its messages and symbolism. Much of the gray area, as you said, is removed. However, I think these changes worked extremely well in condensing the movie for the very different medium that is motion picture. While I loved the film adaptation of Watchmen, I am not sure a direct adaptation would have worked here due to how dense the material is.

Nick: True. I suppose the movie we got was a fine film, whereas a more direct adaptation would have been more of a high risk, high reward scenario.

Greg: It would be interesting to see V adapted as a television series at some point.

Nick: I think that could be a great way to go, although I’m sure the temptation to add things to the story to stretch it out over multiple seasons would be strong.

If nothing else, the novel’s three separate ‘books’ would translate well to television seasons, and a hypothetical third season would be pure bliss for the hardcore V fans if done well.

Well, that’s it for this edition of The Longbook Hunters. Be back here Sept. 19 when we take a look at the first volume of James Robinson’s Starman. And check in next week for our latest edition of Reality Check, in which we’ll delve into the issue of creator rights in comics.