In his 2013 stand-up special, Oh My God, comedian Louis C.K. opined how men are “the worst thing that has ever happened” to women. Actually, we can get a little more specific. If the controversy surrounding Marvel’s July 15 announcement that the moniker of Thor would taken up by a new female character is any indication, it would seem that comic fans are the worst thing that has ever happened to women.

Now, let’s acknowledge that most comic fans are men. Man-children, perhaps, but biologically male, on that much we can agree. And while Louis C.K.’s stinging commentary was delivered in the vein of his typical gallows humor, it was hard to argue with the historical evidence he cited. The comics industry has a proportionally poor track record as well; the grievances suffered by its fictional females are numerous and well-documented. Much of the backlash against Marvel’s new Thor, though, has been no laughing matter. Marvel’s Facebook page offers a cross-section of the very best of the worst. I should be totally desensitized to it by now, but the reminder that I breathe the same air as these particular specimens of humanity remains as sobering as ever.

Here I sit, a male comics reader and a male man, crying foul against the male comics community. Don’t think this irony is lost on me. Nevertheless, there is unavoidably a gender element to the outcry due to the demographics of comics’ readership. Now, far be it from me to get offended on anyone’s behalf. I can’t claim to speak for female readers, aggrieved by this reaction or not. What I can say is that, as both a comics fan and a human being, I find much of the commentary to be childish, embarrassing, and sadly, nothing new. But it needs to stop.

Fair warning, a lot of this will likely come off as preaching to the choir. The people it applies to aren’t going to read it; those who do are already on my side. Russell Sellers wrote a stellar takedown of the issues directly pertaining to the controversy in his July 18 Five Reasons article. I agree with everything he said. In an effort to avoid covering exactly the same ground, this can be thought of as both a companion piece and a jumping-off point. I’ll speak to the Thor reaction (which is already old news by now), but I mostly want to get into some of the broader concerns at play that remain relevant, if only because this keeps happening. Such concerns are universal to every controversy in the comics industry that sees an established character’s race or gender at its crux.

No none thinks of himself as a racist, misogynist, homophobe, or otherwise close-minded bigot. Yet through one’s words and actions, he can irrefutably demonstrate it to be evident. The negative response to Marvel’s new Thor is complicated because two separate issues are getting confused. One of these or the other is almost always at the center of any controversy surrounding a major creative shake-up. However, the two combined and framed by this type of context exposes an underlying, ugly mentality. It’s a kind of vitriol that sits very uncomfortably with me as a comics reader and reflects badly on the industry as a whole. So, here’s my attempt to unpack these issues and separately examine the logical fallacies that contribute to so much negativity.

The first thing we need to talk about when we talk about the small-minded thinking within a certain segment of comics fandom is tradition. Or, more pointedly, how you don’t mess with it. Russell touched upon the cowardly, superstitious nature of comic fans, and he’s right. For all that loyal, diehard fans claim to want change and progress, bemoaning how tired they are of the same-old, same-old, it seems the kind of change they really want to see is in a direction back towards whatever they found most appealing about a long-running property in the first place.

Now, this describes a hypocritical few who demand organic character growth, but only within their extremely biased, narrow confines. There are probably just as many fans who know what they like and are intelligent enough to realize that they shouldn’t pretend to want any deviation from their preferred interpretation of a given character or concept. They might be a bunch of sticks in the mud, but they’ve more or less made their peace with this sentiment. That’s a lot more honest, and easier to contend with. It also describes my feelings on very certain, trivial matters in comics. But I’m trying.

That most appealing, “back-to-basics” quality is entirely subjective to each retro-oriented fan. The simplest answer, though, is: the best depiction of a character is however he was being written when the reader was 14 years old. That’s it. Everyone’s favorite version of everything in comics almost always comes down to trying to recapture the initial burst of exuberance delivered in that first hit. It’s why you have different “camps” of fandom for Superman and his favored origin story (spoiler: I’m a Byrne Guy). Or Spider-Man, and whether he’s fundamentally better as a swingin’ single, or happily married. This is one of the things that makes participating in comics fandom so much fun. Playful jousting over our differences is one thing, but some take it too far and are painfully lacking in perspective. In order to weather the ebbs and flows of the comics industry over time, with sanity in tact, one has to learn to stop letting nostalgia cloud his qualitative judgment and accept the new with the old.

I’ve been at it for over 20 years (which I realize makes me a novice in some circles), but this I am learning. I go a little nuts sometimes. But I also still find a lot to love, and look forward to whatever the future holds for my favorite characters, warts and all. I don’t think there’s anything the industry can do to kill my love for comics as a art form. Having some willingness to let go of the past is a critical component in my willingness to make that statement with any degree of confidence.

That said, when we say change, what we sometimes mean is “change.” Massive, corporate-owned institutions (like the ones making multi-millions of dollars at the box office every year) are famous for practicing the illusion of change. Their concepts can only deviate so much from the longstanding default before inevitably snapping back to a generally-accepted status quo. Far from being damning, there is an art to this and it really is quite a thing of beauty in the right hands. Radically altering a major cultural icon like Batman is typically limited to “killing” him or “replacing” him. These things can make for exciting detours that tend to be met with a bit of resistance nonetheless.

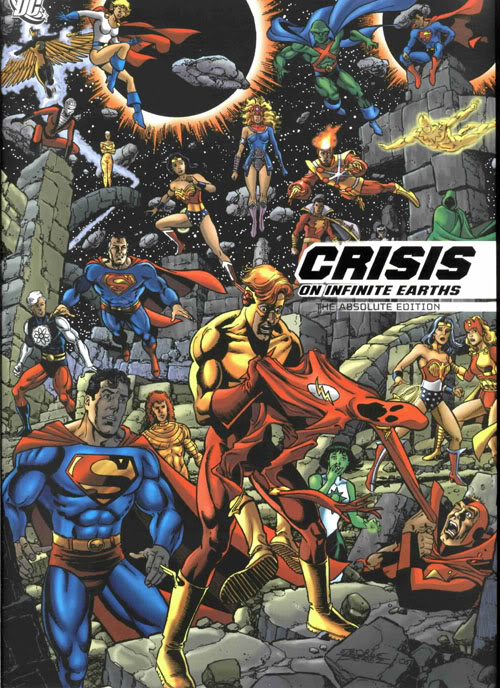

Granted, we have seen some semi-successful experiments in the concept of legacy characters. I’m 30, and Barry Allen’s original tenure as the Flash completed preceded my ability to read. “My” Flash has only ever been his successor, Wally West. Unfortunately, nostalgia vision cuts both ways and this did not stop DC’s management, whose adolescence was spent following Barry Allen’s adventures, from reviving the character. A combination of nostalgia and illusion of change at work. (Sigh. A problem for another day). I am certain that the decision to retire (re: kill) Barry in 1985’s Crisis on Infinite Earths encountered no shortage of opposition. But DC did it, and moved on (or so we thought).

Wally West was an easy, organic choice for the role since he’d been bumming around for years as Barry’s sidekick. Later, DC caught a lot of flack for swapping out Bruce Wayne with newcomer Jean-Paul Valley as Batman in 1993’s Knightfall storyline by canny fans who pointed out that former partner Dick Grayson was, after all, right there. The very next year, DC’s move to replace Hal Jordan with Kyle Rayner, a brand new character invented for the express purpose of taking up the mantle of Green Lantern, so outraged a contingent of fans that they formed a bonafide movement referred to as H.E.A.T.: Hal’s Emerald Attack Team.

Now, remove your palm from your face and consider: it matters not only how, been when you do these things. The changes to Green Lantern took place in the 1990s. The comics readership was exponentially greater than that of the ’80s, when Barry Allen got the heave-ho. The ’90s comics market could support a thing like H.E.A.T. in conjunction with an audience that blissfully thrilled to the adventures of Kyle Rayner, rookie Green Lantern, month-in and month-out. Say what you will about the objectives and methods of the group, but this was a collection of fans who passionately, whilst constructively, voiced their objections.

The current comics marketplace contains arguably the largest concentration of hardcore fans the industry has ever seen. Suffice to say, we’ve been around the block a few times. This is part of why I find reactions to new characters in familiar clothes so disconcerting. We’re supposed to be older and wiser. However, while the readership is a fraction of what it once was, outlets to air one’s grievances are merely a mouse click away. Internet message boards and the like were a novel concept in those days gone by, in contrast to the mass commodity they have grown to become today. They provided a unique opportunity to a resourceful few, lending activist fan groups like H.E.A.T. more credibility than we might assume from a modern vantage point. It also doesn’t hurt that they were willing to put some money where their mouth was.

Widespread adoption of disruptive technology has a leveling effect on society. With respect to the comics community, the lines between “consumer” and “participant” are as blurry as ever–to the point that it feels like that ratio has entirely inverted since comic sales peaked in the ’90s. Indeed, today’s voices of discontent are a lot louder, nastier, and easier to come by. A great many aren’t actually buyers of the product in question, contributing to a great deal of white noise that is difficult to separate from balanced criticism.

The economic environment notwithstanding, I get that the acceptability curve is tougher for brand new concepts and characters, especially when faced with a devoted, built-in fanbase. In the cases of the Flash, Batman, and Green Lantern, their successors–new or old–were all strapping young white guys. But if your replacement hero happens to be of an ethnic or sexual minority, it seems to go down very badly indeed. And the publishers must be braced for an entirely different kind of shit storm.

It’s natural to want to pick apart the reasons behind changing a character’s civilian identity. Let there be no mistake: it is always driven by sales. That’s not cynicism, it’s reality. Cynicism is a large and/or loud mob of comic fans immediately shouting down such a change as token lip service. Gender, race, age, nationality, faith, or sexual orientation are perfectly legitimate ways of differentiating a fictional character. Marvel and DC have the problem that the overwhelming majority of their most popular characters were created in the 1960s, and as such, are disproportionately white and male. “Diversity” in Silver Age comics meant having a girl on the team whose purpose and defining trait was to function as The Girl. These companies should be applauded for making every effort to diversify their character offerings.

(Sidebar: there’s a part of me that wants to say you don’t get a cookie simply for doing something you ought to have been doing [or not doing] all along. However, the entertainment industry in general has been playing catch-up with respect to this deficiency for some time. I propose we commend their baby steps whilst still holding their feet to the fire.)

I might suggest, even, that a company’s reasoning for replacing a character is multifaceted, and if they can kill two birds with one stone by diversifying their line-up plus making more money, that should be quite praiseworthy indeed.

And yet… this does not stop your friendly neighborhood Comic Book Guy from delicately explaining, “I would very much like to see more black and Hispanic characters in comics! But they should be all-new characters, not replacements for the ones we already have!” His compatriots nod and stroke their neckbeards in agreement. You can sort of agree with this logic, innocuous as it sounds. However, it is undermined by two fatal flaws, the first of which is outragously easy to grasp:

New characters don’t sell.

Period. Regardless of their race, gender, whatever. We have to go back to the ’90s to find new characters that still have any real staying power today.

Again, this goes back to the depressingly diminishing revenues of the comics industry. It’s a massive problem that every publisher has to address, but it isn’t necessarily beyond solving, and certainly, doesn’t mean it isn’t worth the effort. There’s something to be said for throwing enough new crap at the wall until something sticks. However, when the path of least resistance is to hitch your new concept to that which is tried and true, it’s a publishing strategy hard to argue against. Especially when you are committed to making sure your new multicultural hero will actually sell. Again I say, bravo. Which brings me to…

Even if new characters didn’t have an abysmal rate of success, there are benefits to be realized in tying them to preexisting concepts. The fact is, there is intrinsic VALUE to the name Spider-Man. Miles Morales, the resident Spider-Man of Marvel’s Ultimate imprint, is a wonderful character who happens to be a black, Hispanic teenager. Spider-Man’s identity as a racial minority is significant, both culturally and commercially. For about 50 years, Marvel has told us that Spider-Man could be anyone behind the mask. It’s an important mark of the character’s enduring relatability. Now, when a black kid just learning to read picks up an issue of Spider-Man, he can actually agree with that sentiment. So when you say that you like Miles, but wish he could be an equally-successful character unrelated Spider-Man, realize: it is a bit like claiming you don’t have a problem with seeing a black person in a position of power, you just wish one of them didn’t have to be your boss.

All this is to say, “Oh my God!” indeed. As in, ohmygod how are we still having this argument in 2014, rather than working through issues of equality that are still badly misunderstood, owing to a basic ignorance of people who are not frequently encountered/represented in basic, everyday interactions, etc. etc. But such is life.

“That’s not how I think, and that’s not what I mean!” you shout. “Replacing Peter Parker with a black Hispanic teenager reeks of tokenism! Peter Parker is already universally representative as Spider-Man!” OK, I just explained why that isn’t true, so what’s your real beef here? “This is a big stupid publicity stunt!” Ahhhh. Here is the second issue we are getting swept up in that applies whenever a high-profile character is “replaced” (and I’m getting tired of the figurative quotation marks too, but bear with me). It holds true no matter who does the replacing.

We have established that many comic fans don’t like change, and they don’t like it in a way that unfortunately manifests as intolerance. If they don’t like change, they like publicity stunts even less, and in a way that unfortunately manifests as stupidity. I’ve been dancing around this one a bit already because the two go hand-in-hand so frequently. The way it works is that when you’re a publisher and you’re going to be maiming, killing, marrying, or replacing one of your major characters (as a publisher is wont to do), you’ll try to make a lot of noise about it. You’ll hope the announcement lands on a slow news day. Even so, you aren’t entirely sure who is going to take the bait.

The comics industry has a long and perverse relationship with the mainstream media. Essentially, as far as they’re concerned, there’s no such thing as bad publicity. Mostly, they’re right. At a time when publishers are desperate to move the books that they can, it doesn’t hurt to get as many eyes as possible on the big event du jour. The problem lies in the fact that press releases almost always mean one thing to the comics buying audience and another to the general public. The journeyman comics fan is fairly accustomed to reading between the lines to decipher the real story. To us, this is nothing new. So why do we always act like it is?

“This won’t last!” You seethe with rage. “Twelve months, tops, and it’ll be back to the same old shit, MARK MY WORDS!” Unless these words are spoken to a reassure a despondent fan convinced that things will never be the same again, then I’m afraid you’re arguing with a strawman, fella. Of course things will be the same again. In comics, things are always the same again. It’s just part of the fun to be had with that whole illusion of change conceit. Remarkably, those twelve months transpire, and your prophecy is fulfilled! “See, it crashed out of the gate, just like I said! What a failure. When will Marvel learn their lesson?”

Never mind the fact this was always part of the plan. That the creators didn’t let the cat out of the bag by telling you on Twitter and Formspring doesn’t change this reality. Likewise, never mind that as far as the critical acclaim and bottom line is concerned, it was anything but a failure. In fact, by all accounts, the mainstream publicity did exactly what it set out to do. The activist fan doesn’t let such facts get in the way of his need for righteous superiority.

Seriously, when’s the last time a calculated publicity stunt has blown up in Marvel’s face? (and I’m singling out Marvel because Thor is their character). I’m not being facetious. Miles Morales as Spider-Man turned out to be reinvigorating for the Ultimate imprint and has come to be warmly embraced by the readers who don’t see the rudimentary hurdle of replacing Peter Parker as a deal-breaker. In 2007, Steve Rogers’ death and subsequent replacement as Captain America made national headlines. Today, he’s back from the dead and back in the uniform, to the shock of no one. It does not detract from what was a fantastic saga spanning several years. As Marvel intended from its inception. This was not back-pedaling. This was not a bait-and-switch. This was the story the company wanted to tell. It also placed Bucky Barnes, Steve’s substitute as Cap, in a high-profile role, allowing him to subsequently springboard into his own series with ease. I’ll bet that was no coincidence either, yet it sadly goes overlooked by the naysayers so frequently.

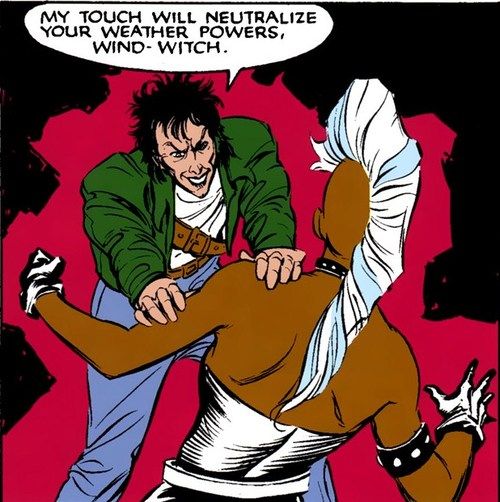

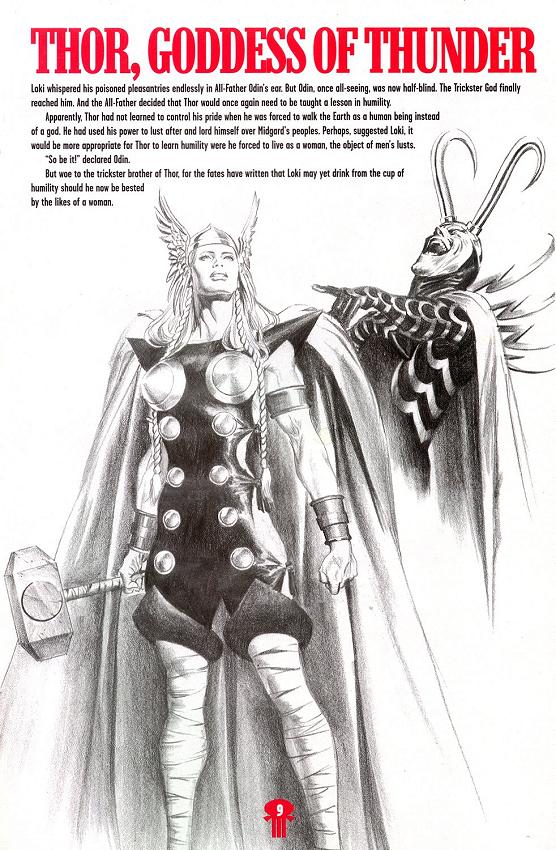

Let’s consider as well that this is far from an original idea. In fact, its redundant nature is a principal criticism cited by many of the detractors. There is some legitimacy to this concern, true; the dearth of original storytelling in superhero comics is a long and separate conversation. More pertinent to this discussion is how those previous attempts at mucking about with the character have been received. It isn’t the first time Thor has been benched. It isn’t even the first time he’s become a woman… quite literally, in fact.

Generally, couching a major change within an alternate reality version of a character can be viewed as an isolated technicality that doesn’t “count” (except when it does). Otherwise, the change is temporary and the character reverts to form.

Irrespective of the circumstances, none of these other transformations were considered a big deal because Marvel didn’t go out of its way to sell them as a big deal. For that matter, with Marvel’s wildly lucrative shared cinematic universe more than a decade out, Thor himself wasn’t a big deal. What’s different this time around is the method of delivery. In his piece, Russell nicely dissected the entitlement mentality within the fan community that simply seems to resent their cherished pastime making the leap to the mainstream. In essence, they are allowing the media to consume the message.

The news was broken on The View, where we learned that the new female Thor will be stepping into the spotlight when Original Recipe Thor is deemed unworthy, and thus, no longer able to stake the claim as “God of Thunder.” To the uninitiated, this might be viewed as exactly as big a deal as Marvel says it is. For those of us more accustomed to these kinds of things, we have a character that Marvel is clearly wanting to push very hard and in whom they are investing tremendous resources to ensure that success. More importantly, The View is a program watched by about three million people daily. I would venture to guess there isn’t a great deal of overlap between its viewership (harhar) and comic buyers. If even a tiny percentage of that audience starts buying the series, it’s a huge boon for Marvel. Do we really think those new readers are going to feel cheated by a false promise if this new character is no longer Thor a year from now? If the story is consistently engrossing and excellent, certainly not. The overall quality control and continued presence of regular writer Jason Aaron all but assures that it will be.

The jury is out on whether the informed public will translate to new buyers. Having a highly visible platform gives Marvel a tremendous opportunity, though, so it’s worth a shot. Far from alienating anyone, the company is relying on their current readership to be savvy enough to recognize the endgame. This character isn’t going anywhere. Like the story of Bucky as Captain America, it’s simply the first stage of her evolution. If handled respectfully (and given the commitment to this development, I believe she will be), any new readers will presumably follow the character in whatever direction she takes, all while the Thor we have come to know and love gets back in the saddle. This does, at worst, no harm, and at best, increases the readership. How can it not be counted as a win for everyone? Judging from Marvel’s past success in employing this strategy, I’m betting that’s exactly what they’re counting on and we have every reason to trust that they’ll pull it off.

Likely, the jaded comics fan is cognizant of all this, yet still cannot help his argument from being confused with that of mouth-breathing, sexist louse. How might he best temper his argument? Russell Sellers painted a dreary picture for us in his essay, presenting a scenario of a misguided fan telling his daughter that Thor can only ever be a man, and therefore, is unsuitable to her interests. We can apply this examination to the topic of inclusiveness within the comics community as a whole. Imagine this enraged fan has not just a daughter — but a sister, a wife, a girlfriend, a platonic female friend, or heck, a mother — who is enlivened by the news of a female Thor to the point of being willing to give this whole comics business a shot. “Don’t get too attached!” he shouts, “She’ll be fucking gone in six months!” The new hypothetical female reader of the new female Thor will be out in an actual six seconds.

We see how damaging this attitude is, both for its potential to harm someone’s self-worth, like Russell pointed out, and for the exclusionary effect it perpetuates within the industry. There are enough barriers to entry as it is without the community itself contributing to them. A better response to the curious new potential reader would be, “It should make for a very interesting development. Would you like a ride to the comic shop, or need help navigating Comixology?”

I’ve noted how comics publishers sometimes like to hedge their bets by limiting changes to alternate-universe versions of their major characters. In this way, they can have their cake and eat it by making headlines proclaiming “Thor is now a WOMAN!” and at the same time diplomatically reassuring the built-in audience that it isn’t the “real” character. Calling out such a compromise as disingenuous is a legitimate form of criticism. I’m pleased that isn’t the case here, and Marvel hasn’t otherwise provided itself with an easy “out.” It leads us to conclude that their intent is to exploit the brand value of Thor to serve as a backdoor pilot for this new female character. I have no delusions it is intended to be permanent, so I’m left feeling intrigued by the twists and turns the story will take and how it will ultimately play out. At the end of the day, I look forward to the promise of a more-diverse and accessible Marvel Universe.

I’m not suggesting that a publisher should get a free pass on any criticism as long as a new replacement hero and/or the subject of a much ballyhooed PR campaign is a minority. Rather, we ought to take a step back and be mindful of the bigger picture and historical basis. Shake-up (and gender-bending!) is nothing new for Thor. All that’s really changed is the character’s profile and Marvel’s fortunes in the eyes of the general public. It remains a story like any other, one that’s been told many times over (because haven’t they all?), to be judged on its merits.

On an entirely emotional level, it saddens me to see this kind of behavior from comic fans particularly. We are all, in one way or another, heavily invested in a fringe interest to which the majority of the population is oblivious or outright dismissive. Don’t we all feel kind of put-upon and different from society at large? I am absolutely not trying to equate the “struggles” of (let’s go ahead and say it) nerdy comic fans with the lifelong, institutionalized oppression faced by women and minority groups, but simply: at the bare minimum, it seems like we should be a lot more sympathetic to these concerns.

I will never know the experience of a black, female comics reader; but I do know that comics have helped get me through some of my personal hardships over the years. So often, comics provide a concept that speaks to my current situation or validates my feelings, personifying some inner voice that reassures me I’m not crazy and I’m not alone. I have no doubt that the series I find this deep, personal connection in also intersects with the interests of the black, female reader I’ve never met who lives clear across the country. It’s something we value, perhaps for different reasons, and have in common without ever knowing it. Corny as it sounds, it’s a remarkably unifying ability of this niche medium.

It would be unfortunate to highlight the examples of poor treatment inflicted upon female characters in comics at the exclusion of the positive portrayals. Because it’s obligatory to mention the X-Men when talking gender theory in comics, have we forgotten about the character development of Storm? When she wasn’t shutting down Wolverine (courtesy of the Wednesday Walk!), comics’ preeminent African-American super-heroine managed to kick ass (with or without her powers) and lead the team as they rode a wave of popularity that would ultimately position the series as the clear industry leader.

There’s a reason why the X-Men resonated with so many people, and it has little to do with their selection of spandex. The concept’s message of equality, shrewdly employed through use of a broad metaphor, was taken to heart by readers of every race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender. The X-Men’s success offers the most decisive evidence that diversity of characters is a good thing for the marketplace. It lovingly illustrates the power that comics command as an inclusive, rather than an exclusive, club.

Of course, X-Men isn’t an outlier in this regard. What about the likes of Black Widow, Agent Carter, and Renee Montoya? Jessica Jones, Barbara Gordon, Monica Rambeau, or the Huntress? We can look to Thor’s own supporting cast, which includes Jane Foster, Sif, and Valkyrie. Marvel’s new teenage Muslim-American Ms. Marvel could similarly make a big impact, if given the chance. Point being, readers are used to depictions of strong female characters in comics and embrace them where they find them. For that reason, I reject that notion that comics fans are inherently as assholish as reaction to the new Thor would lead one to believe. I just wish we didn’t keep having to knock down, condemn, and distance ourselves from the hateful words of a loud, tragic portion of the community.

I suppose using historical precedent to make the generalization that comics fans should actually be thought of as more open-minded than the population as a whole is, on principle, just as wrong as mischaracterizing them as a bunch of basement-dwelling losers. The reality is a lot more nuanced. Optimistically, I believe that the majority of those speaking out against the new Thor do not truly harbor any ill-will towards women, openly or subconsciously. But they could do well to think before they speak. By dropping their stubborn adherence to the status quo, or looking past the relatively minor annoyance of comics as PR events, the significance of what Marvel is trying to achieve may be revealed. Significance, perhaps not to the jaded comics fan (who, let’s face it, isn’t going anywhere despite his grousing), but to the potential new reader next to him. This has nothing to do with kowtowing to political correctness and everything to do with behaving like a decent human being.

I hope I’ve made clear that not all criticism surrounding the announcement of the new Thor is simply misogynistic and without worth. Some of it is perfectly valid. Some of it is not intentionally sexist, but sure manages to cross that line nonetheless. A lot of these fall into the category of frustrating, knee-jerk responses that basically amount to beating a dead horse. These types of brief, thoughtless, unproductive responses are so infuriating because they do not hold up to scrutiny, espouse a double standard, and have a net negative effect. The ridiculous ease with which anyone can express the most banal possible response via social media contributes to a lot of the pile-on. Whenever I’m tempted to dismiss an entire channel of communications (i.e. every comments section on the Internet), I have to remind myself that we would’ve seen the same behavior had the technology existed in the “good old days” of comics fandom.

We can’t have gotten this far without recognizing that characters will always be (temporarily) replaced, and comics publishers will always attempt to drum up as much publicity in doing so as possible. Illusion of change is the only constant. It’s just one, long, circular ride. So what if they sideline the heteronormative, musclebound, Aryan model of masculinity for a few months as the latest expression of the trend. If, in the process of embarking on that journey, one young girl manages to feel just a little less marginalized, and a little more powerful, I think it’s well worth taking.