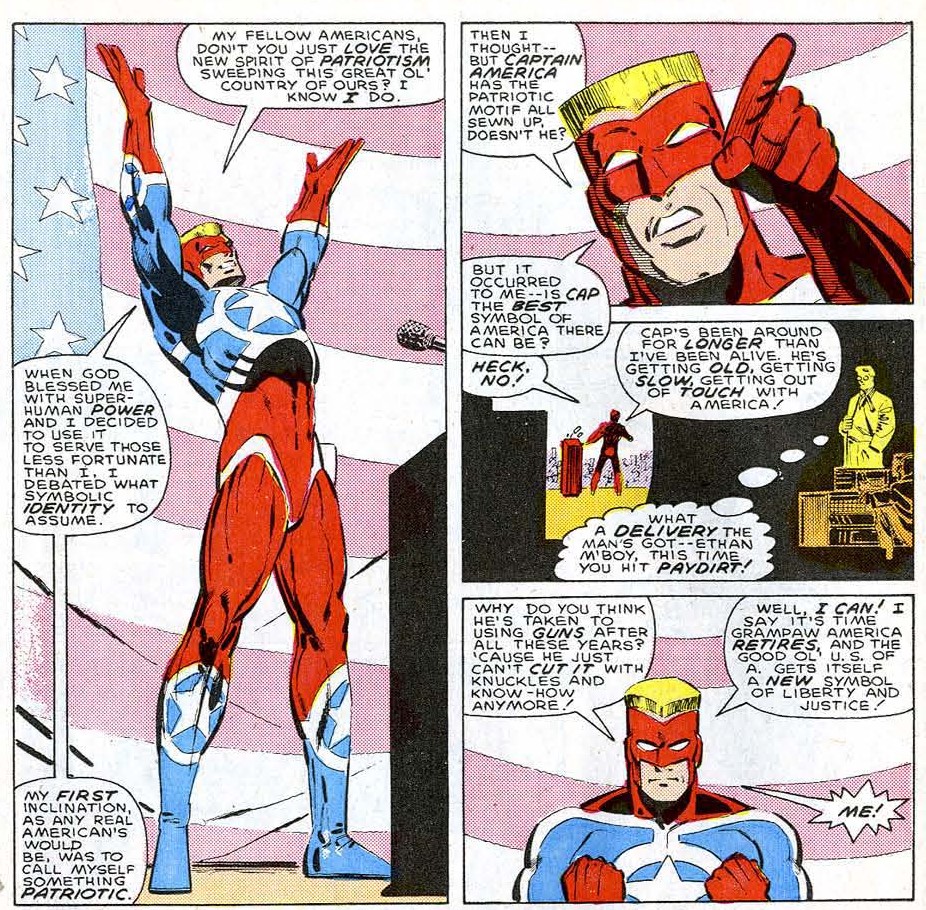

Every larger-than-life hero needs an opposite number as a means of reasserting his core values. For most of his existence, arch-nemesis the Red Skull occupied this role for Captain America. But by 1986, the Red Skull’s Nazism felt obsolete as a contrast to the more layered character Cap had grown into. Having populated the series with characters that allow Steve Rogers (and, admittedly, the writer himself) to function as a sounding board for the major causes of the day, Gruenwald sets out to provide a more relevant flip-side to Captain America himself in the form of John Walker, the Super-Patriot.

The Super-Patriot was built from the ground up to be everything Steve Rogers was not. Where Rogers was originally frail and sickly, John Walker was fit and hearty; where Rogers was from the urban-poor, Walker was rural middle-class; where Rogers was even-keeled and idealistic, Walker was loud-mouthed and realistic. As Super Patriot, Walker is also super-powered in opposition to Cap’s (peak) human physique. They clash, and the battle proves indecisive both physically and philosophically. Arguably, the Super-Patriot offers a more fitting connotation of what “Captain America” stands for in 1980s America. This attracts the attention of the U.S. government’s Commission on Superhuman Activities (CSA), another Gruenwald creation.

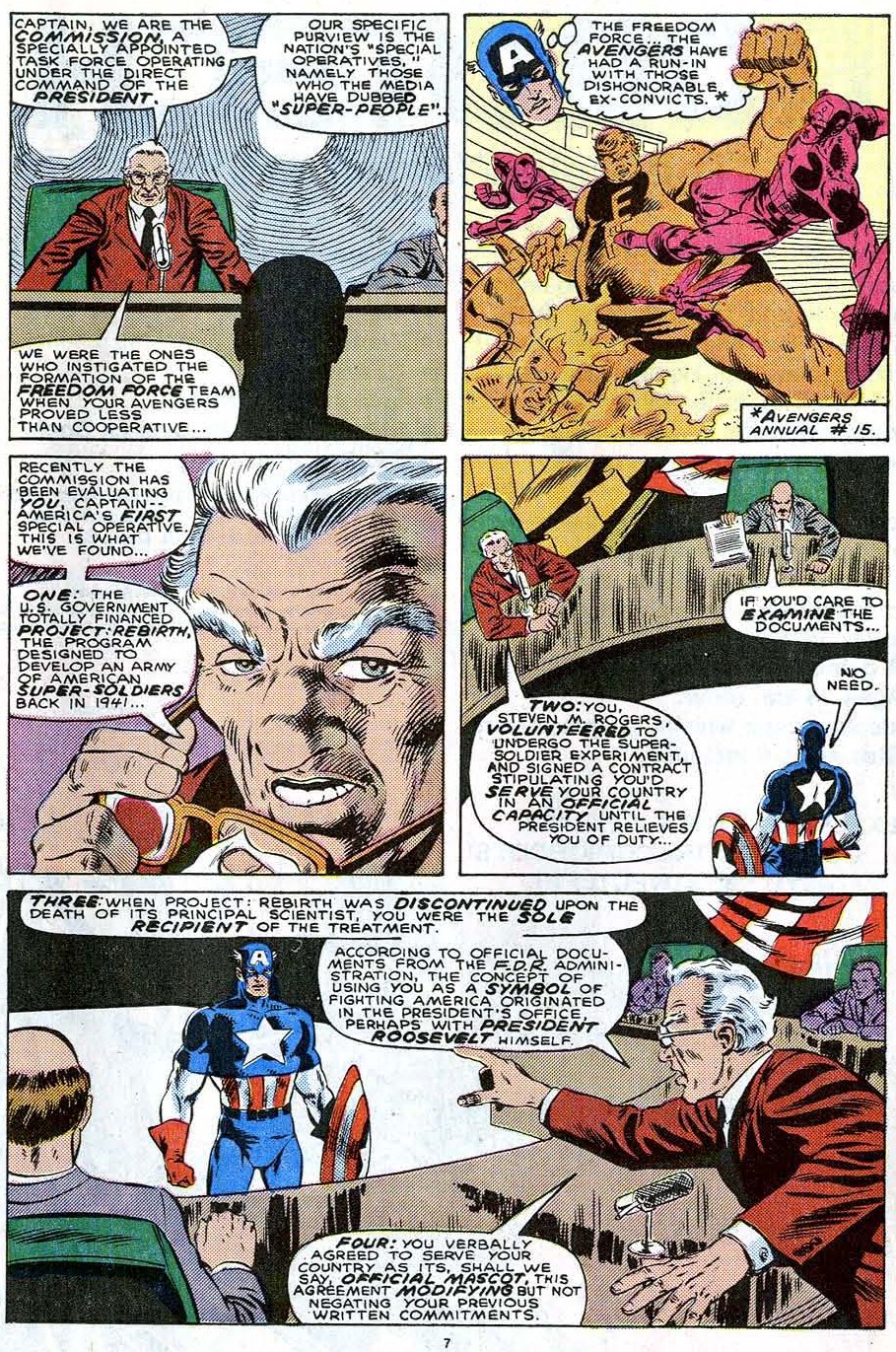

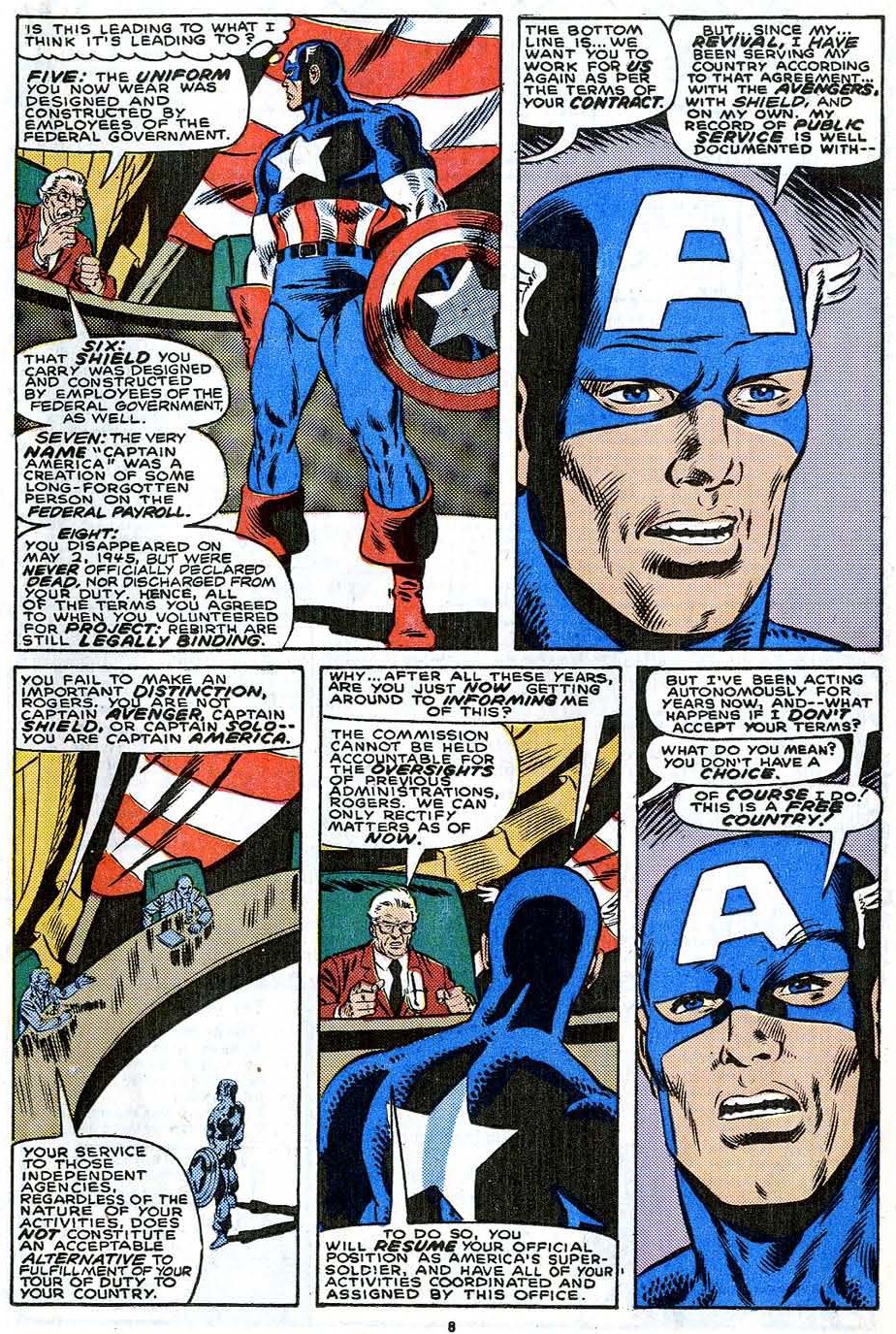

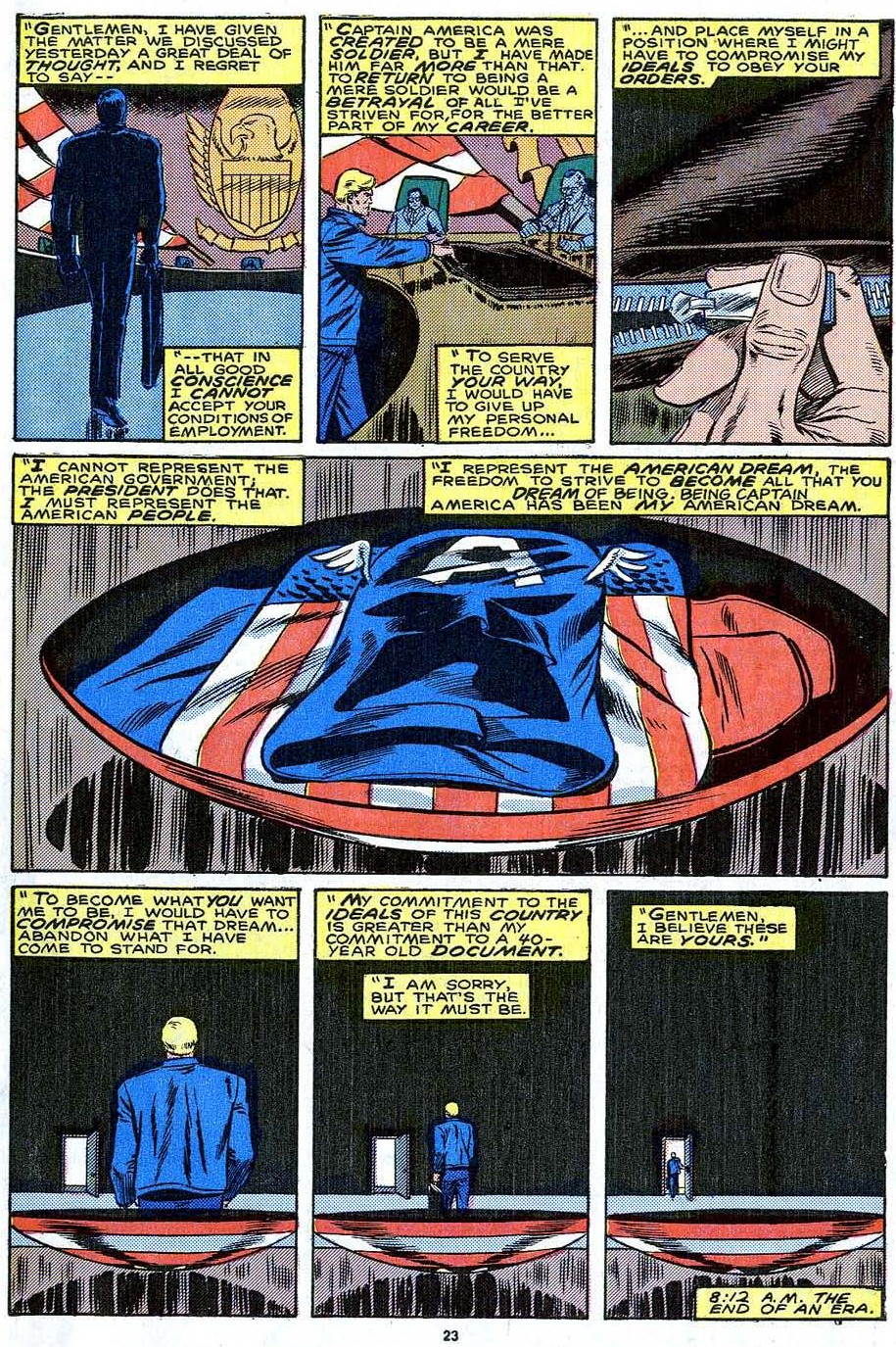

Gruenwald’s CSA portrays a government rife with bureaucratic excess, operating under a businesslike mentality that anything can be bought, sold, or repurposed — including the American Dream. Steve Rogers disagrees. Having long since reconciled that he can represent the ideals of his country without representing any particular administration, he once again relinquishes his costume and shield. A monumental event in the context of the series, as far as Cap himself is concerned, this is little more than a bad day at the office. He lays down his instruments but not his resolve. After a bit of soul-searching (absent the melodramatic, total demoralization of Englehart’s similar stories a decade earlier), he dons a new red, white, and black uniform as simply “The Captain” and resumes his work.

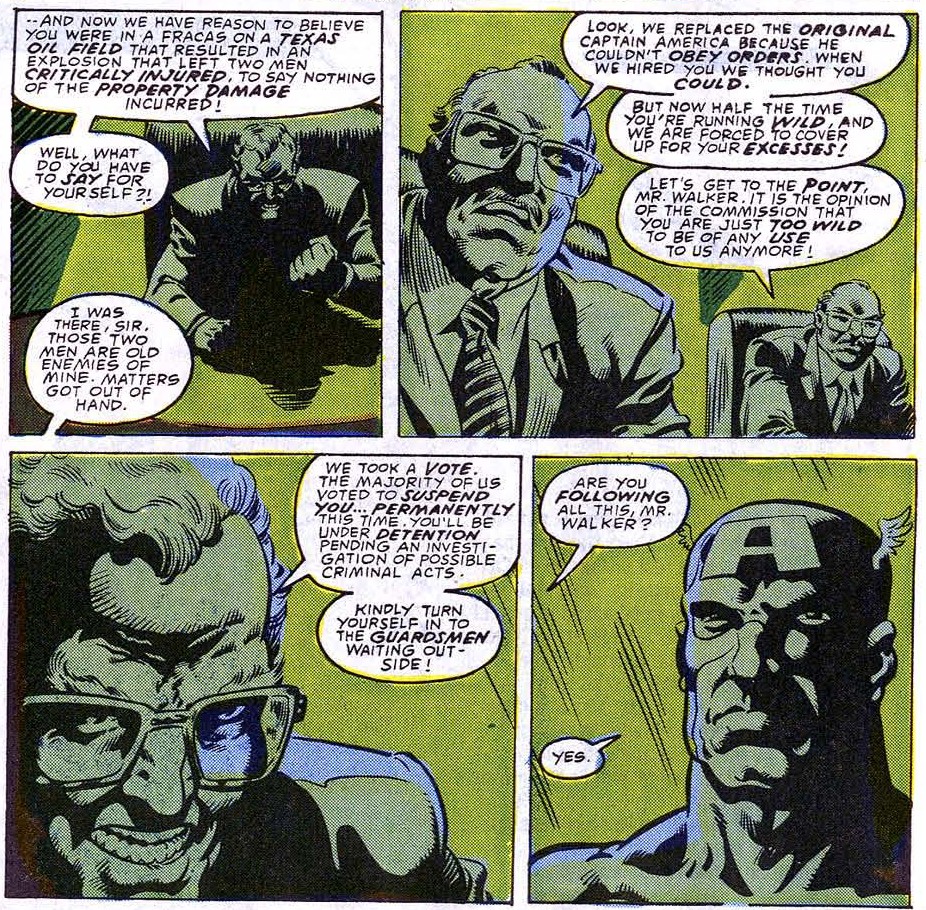

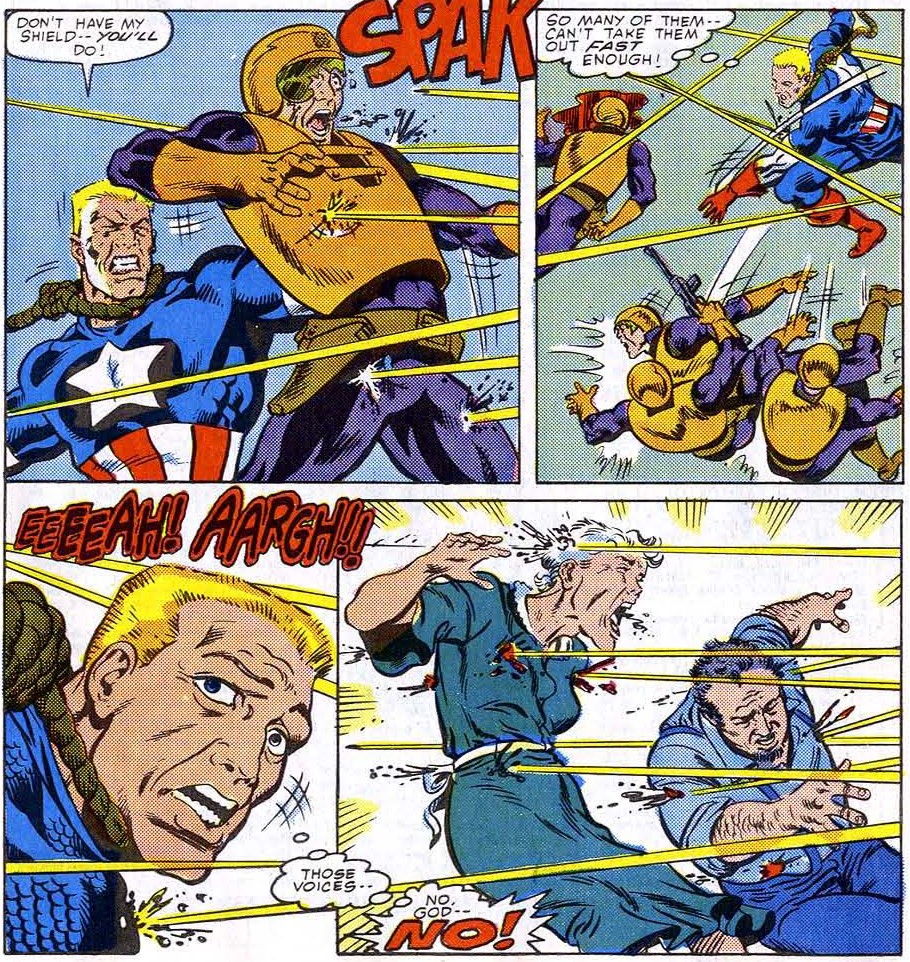

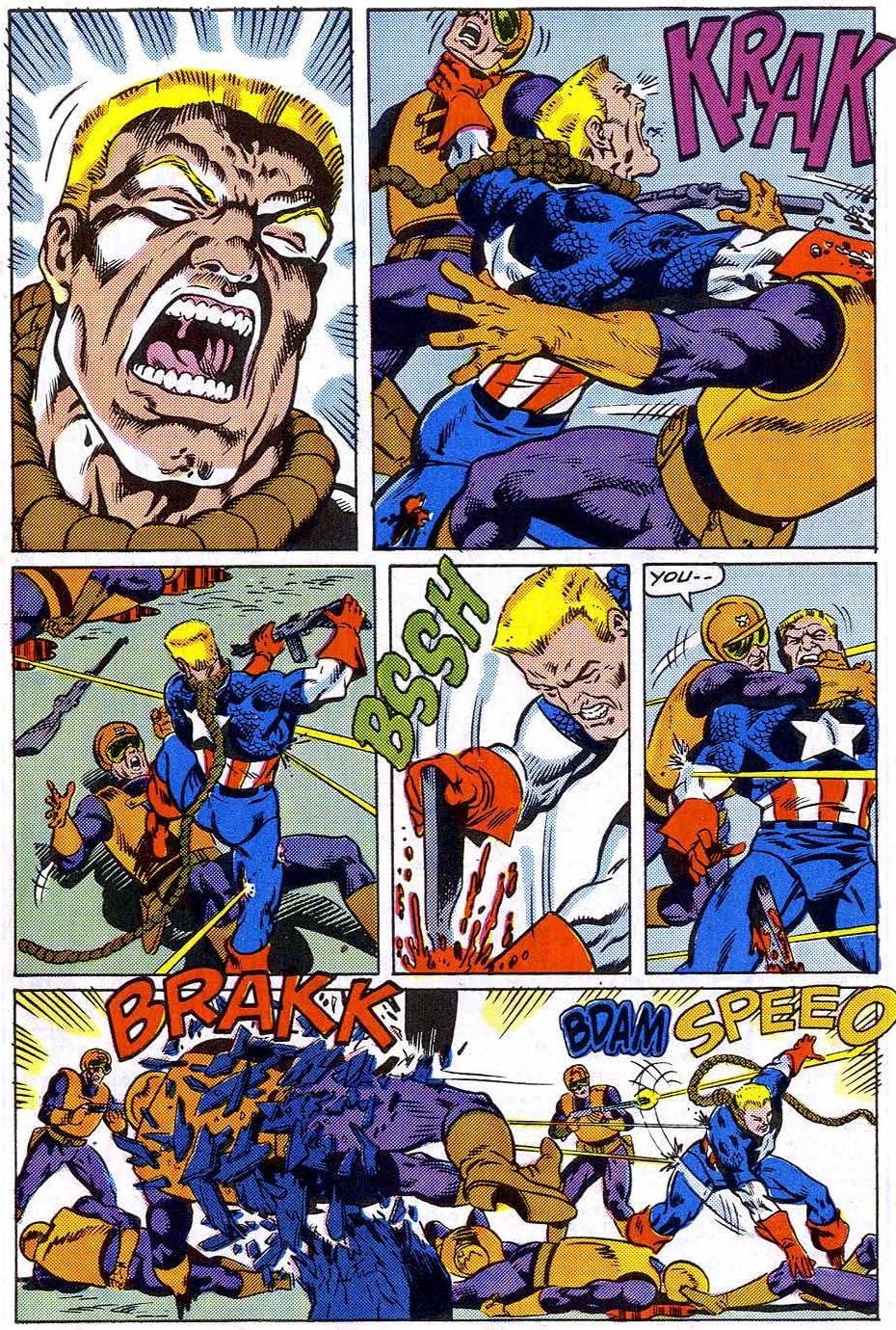

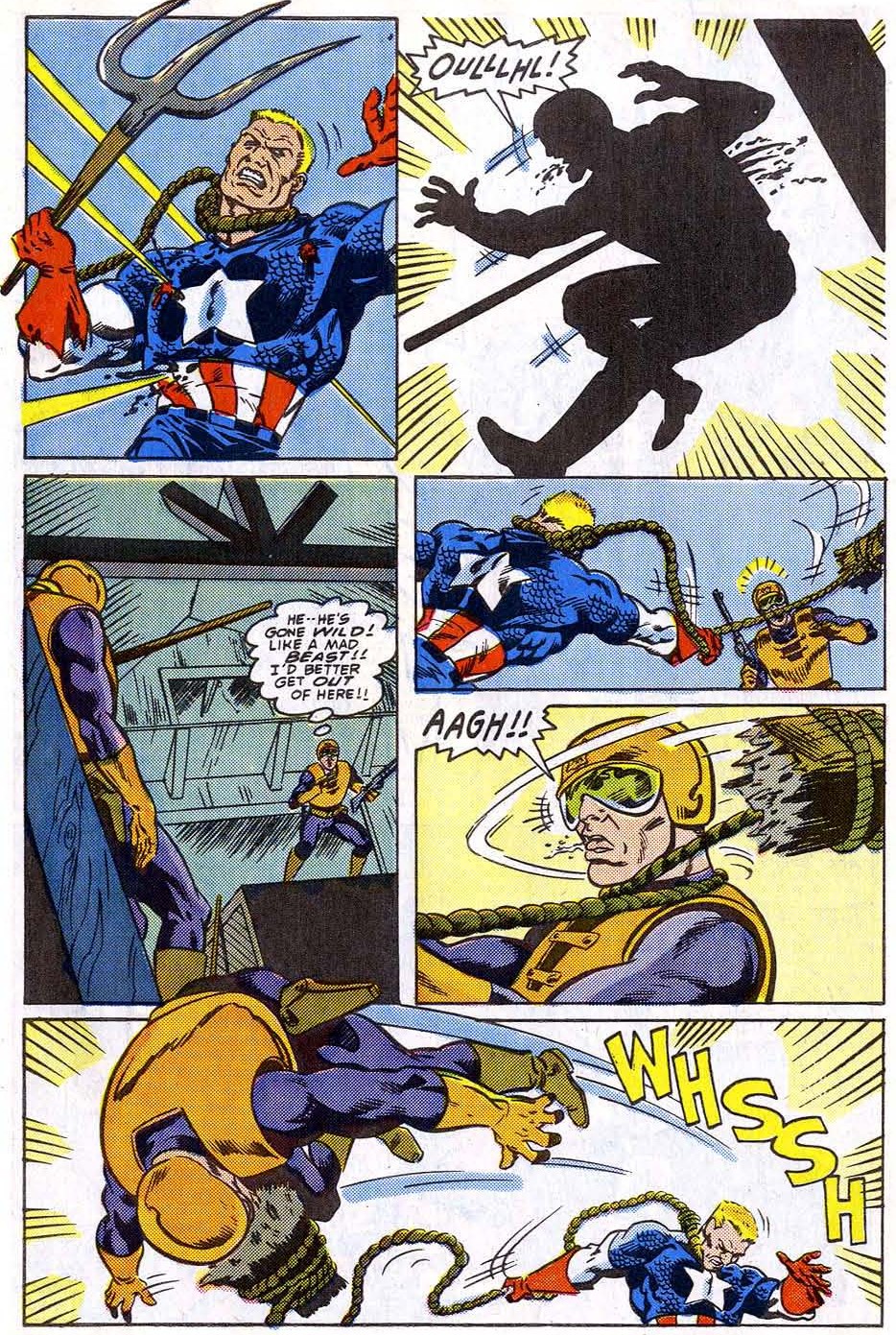

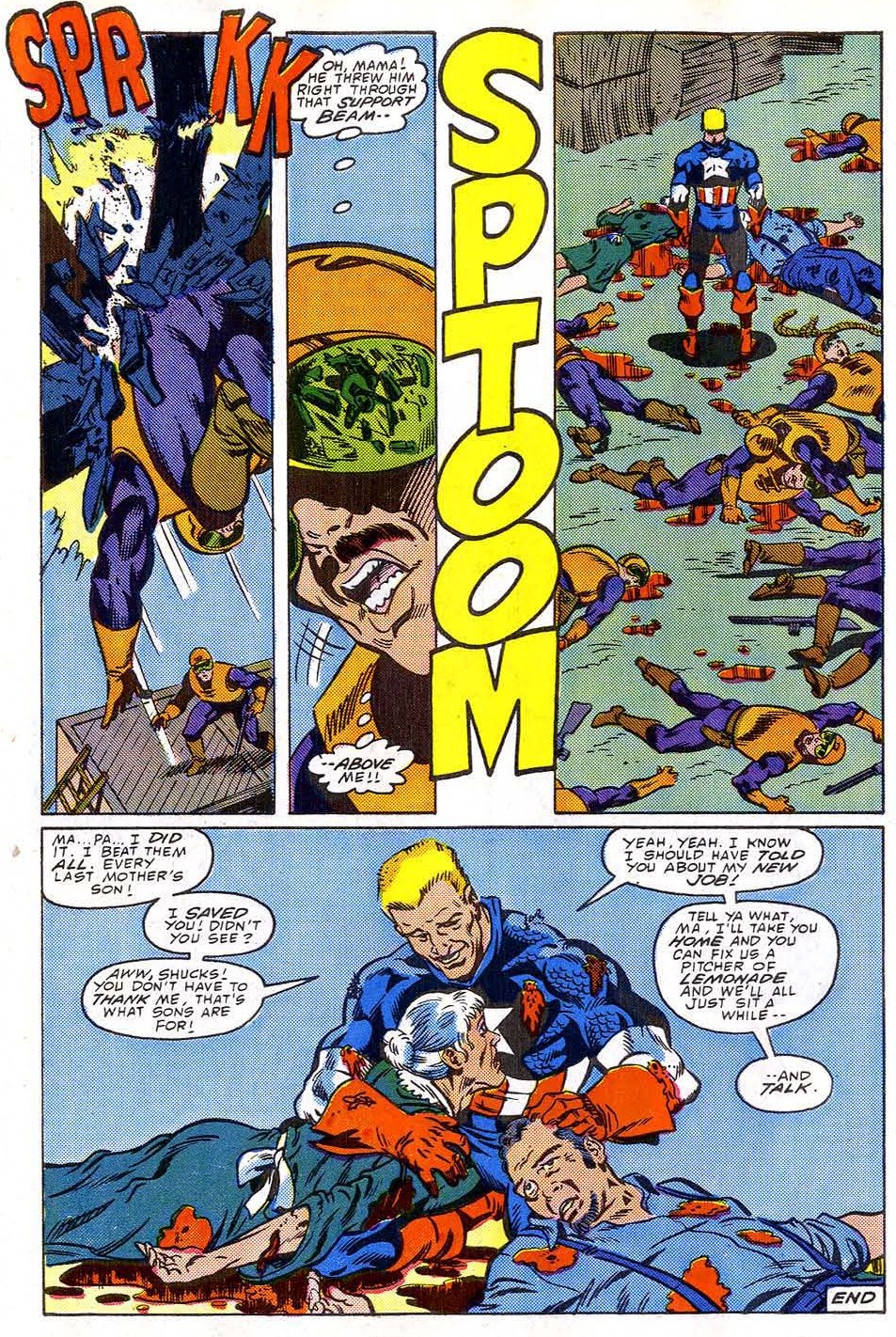

Meanwhile, the CSA plugs a new operative into the suit as Captain America — the former Super-Patriot, John Walker. Walker becomes increasingly jaded, violent, and unhinged. He brutalizes several targets on missions at the CSA’s behest, then berates himself for failing to live up to the standard set by his predecessor. The government realizes only too late what they’ve lost through their short-sightedness, to disastrous results. It all comes to a head when Walker’s shady former partners expose his identity on national television, resulting in his parents being taken hostage by domestic terrorist group, the Watchdogs. Against orders, Walker gives himself up and tries to resolve the conflict single-handedly. A melee breaks out and his parents are killed in the crossfire. He responds by slaughtering the entire roomful of Watchdog operatives.

Meanwhile, the CSA plugs a new operative into the suit as Captain America — the former Super-Patriot, John Walker. Walker becomes increasingly jaded, violent, and unhinged. He brutalizes several targets on missions at the CSA’s behest, then berates himself for failing to live up to the standard set by his predecessor. The government realizes only too late what they’ve lost through their short-sightedness, to disastrous results. It all comes to a head when Walker’s shady former partners expose his identity on national television, resulting in his parents being taken hostage by domestic terrorist group, the Watchdogs. Against orders, Walker gives himself up and tries to resolve the conflict single-handedly. A melee breaks out and his parents are killed in the crossfire. He responds by slaughtering the entire roomful of Watchdog operatives.

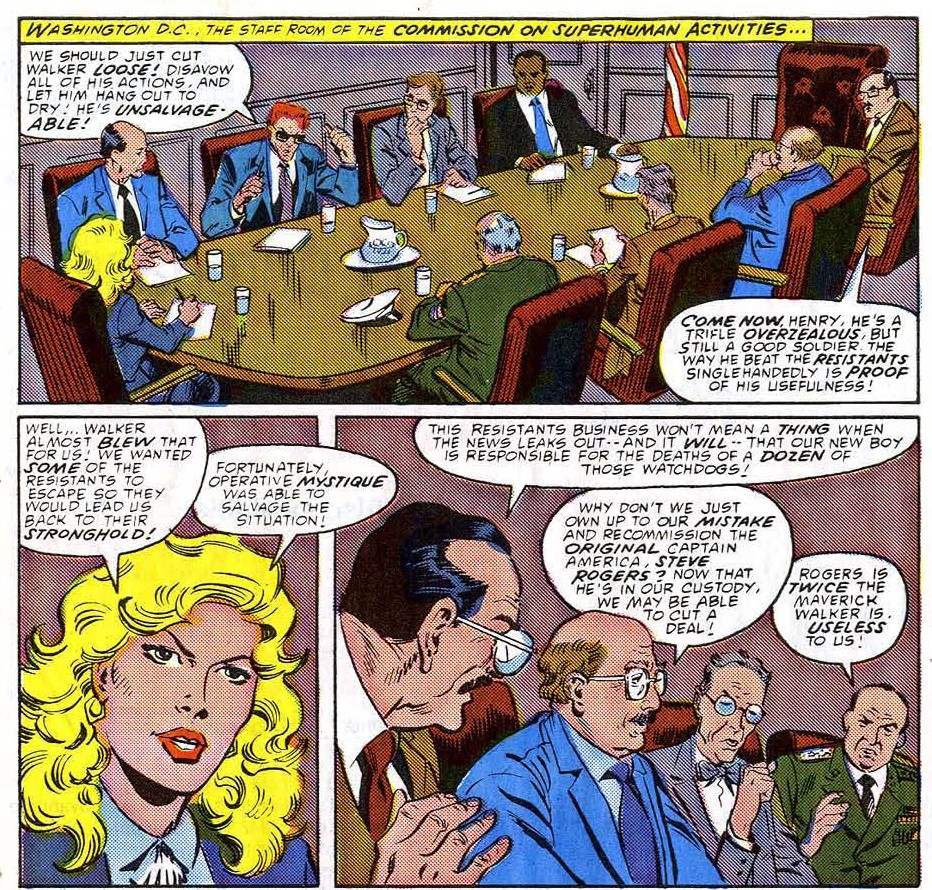

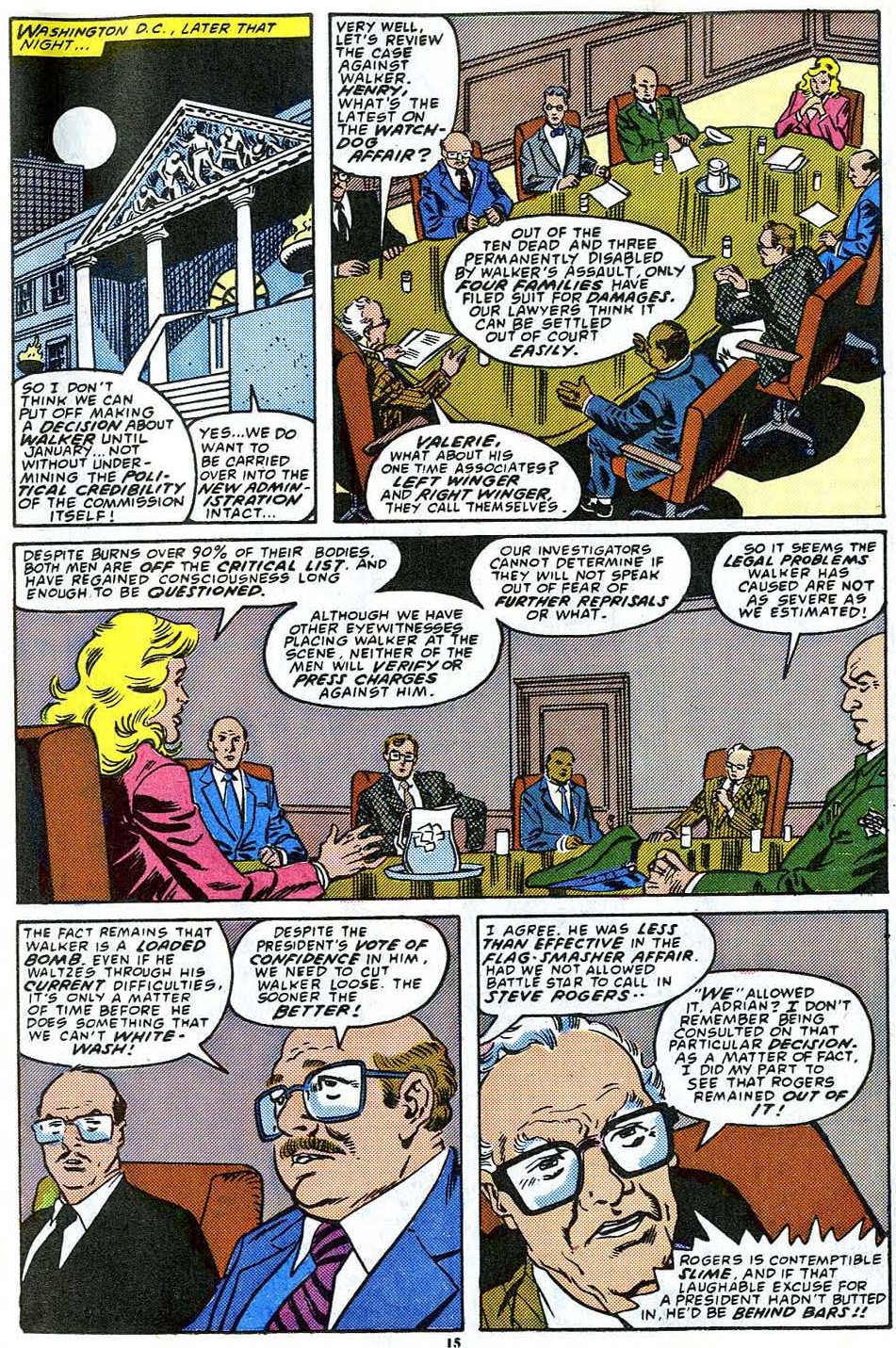

Walker is retained as Captain America for the moment, but continues to employ lethal force. Meanwhile, Steve Rogers acts outside the government’s purview as the Captain and is regarded as a vigilante. He soon exposes a conspiracy within the ranks of the Commission. The Captain fights his way past an unknowing pawn in John Walker, in the process learning the extent of his would-be replacement’s transgressions. The sniveling yes-men in the Commission then attempt to correct their mistake, throwing Walker under the bus.

Walker is retained as Captain America for the moment, but continues to employ lethal force. Meanwhile, Steve Rogers acts outside the government’s purview as the Captain and is regarded as a vigilante. He soon exposes a conspiracy within the ranks of the Commission. The Captain fights his way past an unknowing pawn in John Walker, in the process learning the extent of his would-be replacement’s transgressions. The sniveling yes-men in the Commission then attempt to correct their mistake, throwing Walker under the bus.

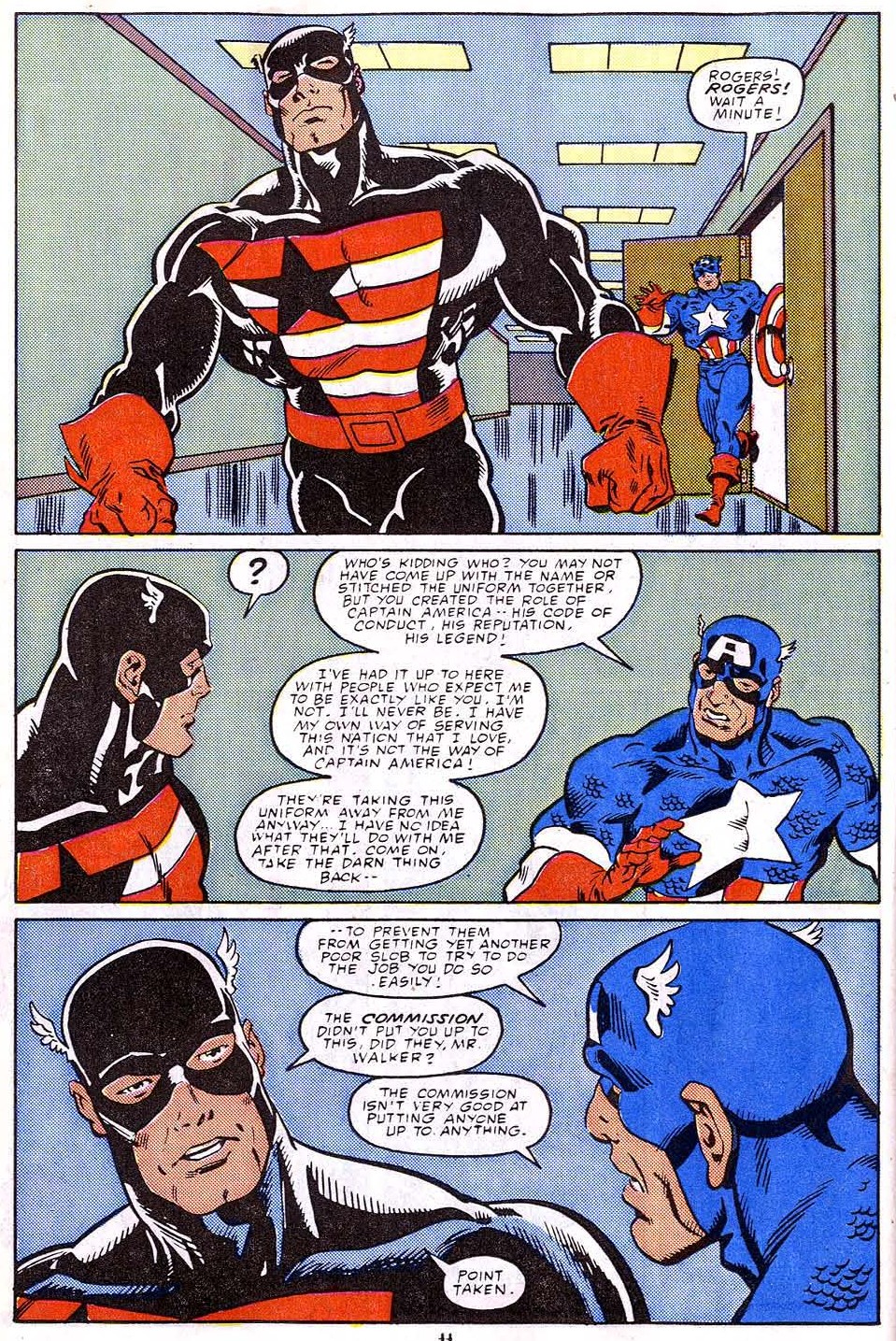

With Walker reigned in, the government expects Steve Rogers to quietly pick up where he left off. The Captain has other ideas. It is Walker, of all people, who convinces Steve to reclaim his rightful place as Captain America. Even he recognizes the inherent value in what Captain America has come to symbolize, pleading that it is too important to be undermined and tainted by a cynical government agency. Being Captain America is a responsibility to be undertaken only by the absolute best person for the job. Through it all, Gruenwald takes care to paint Walker not as an out-and-out villain, but as a troubled man co-opted by an unscrupulous bureaucracy. It’s a poignant story that pulls back the superficial veneer of chest-thumping, blind patriotism that at first seems intrinsic to a character called Captain America.

Key throughout all of Mark Gruenwald’s contributions to the Captain America mythos was the critical component of moral ambiguity. He showed how fundamentally noble agendas could be twisted to frightening extremes. The traditionally black-or-white Steve Rogers was dropped into the reality of a world that was shades of gray. This was the ultimate test of his mettle. How would he respond to a crisis without the one, clear, right solution? Would he bend to accommodate the prevailing trends of the times? Or would he draw upon his accumulated wisdom and experience, confident that the values he practiced were not so fickle? It was Gruenwald’s willingness to invite these questions that made his run such a joy to behold. And as the character entered the ’90s, the answers wouldn’t come any easier.

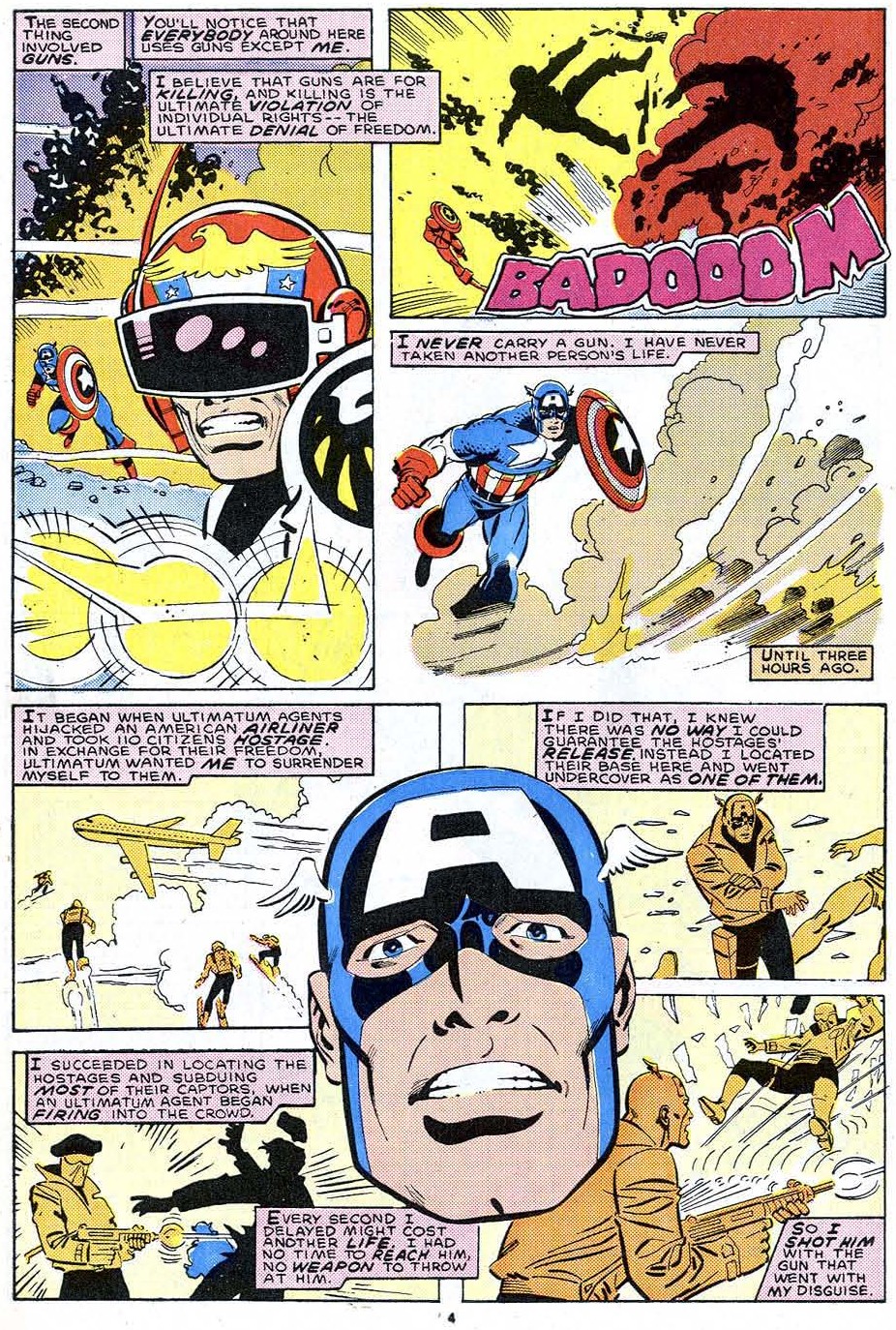

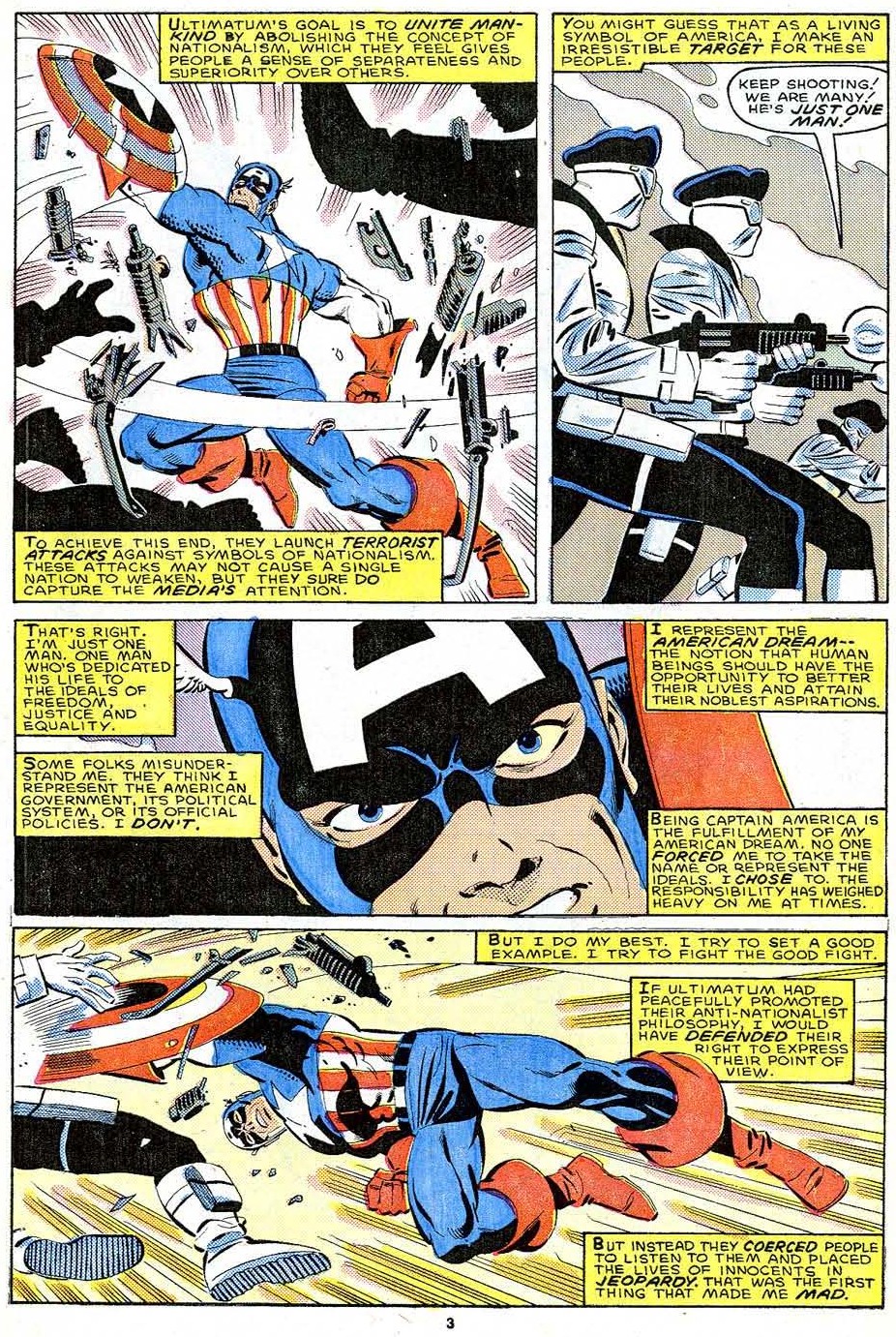

For all of Gruenwald’s praiseworthy efforts, it was during his ten-year tenure that the depiction of Steve Rogers as the polarizing figure I refer to as “Saint Cap” gradually surfaced. In story after story, Steve Rogers’ indomitable will was reinforced and his unassailable decency persevered. The regularity of company-wide crossover events like Secret Wars, Acts of Vengeance, and Operation: Galactic Storm cemented him as the leader of not only the Avengers, but the entirety of Marvel’s super-powered community. While such positive attributes were well-earned by the character, they also had the effect of robbing him of a certain fallibility. Occasionally, this strained credibility altogether. In one such story, Cap agonizes over his use of lethal force to stop an ULTIMATUM agent, breaking his stance that he had “never taken another person’s life.” For America’s World War II super soldier, this claim seemed dubious, to say the least.

Towards the end, Gruenwald’s stories took a turn for the… unusual, to put it kindly. If Cap’s psychological make-up was too resilient to warp, then Gruenwald made up for it by putting the character through several bizarre physical changes. Brief, goofy stories would see Cap turned into a teenager, a drug addict (not quite), a woman (almost), and a werewolf (bringing us full circle back to the immortal “Cap-Wolf”). Now, I’m tempted to claim such tales were inspired by a certain enthusiasm for body horror within the culture. This took off as a genre convention in the late ’80s and early ’90s, and these things are not without their catalysts. We could look to topical paranoia surrounding the anti-aging movement, pollution, birth defects, the HIV/AIDS scare, and so on. But I think I think I’ll put these later adventures down to dumb fun, and leave it at that. The point is, Gruenwald balanced the heady tone of his serious stories with some lighthearted, satirical romps to nice effect.

Towards the end, Gruenwald’s stories took a turn for the… unusual, to put it kindly. If Cap’s psychological make-up was too resilient to warp, then Gruenwald made up for it by putting the character through several bizarre physical changes. Brief, goofy stories would see Cap turned into a teenager, a drug addict (not quite), a woman (almost), and a werewolf (bringing us full circle back to the immortal “Cap-Wolf”). Now, I’m tempted to claim such tales were inspired by a certain enthusiasm for body horror within the culture. This took off as a genre convention in the late ’80s and early ’90s, and these things are not without their catalysts. We could look to topical paranoia surrounding the anti-aging movement, pollution, birth defects, the HIV/AIDS scare, and so on. But I think I think I’ll put these later adventures down to dumb fun, and leave it at that. The point is, Gruenwald balanced the heady tone of his serious stories with some lighthearted, satirical romps to nice effect.